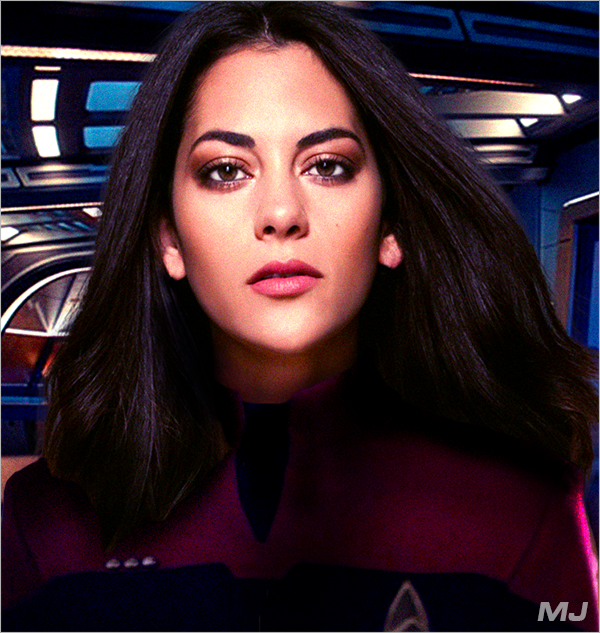

Constellation was configured with a far smaller gymnasium than the laboratory city of Taes’ last command. The use of space aboard a Constitution III-class starship had been strictly optimised for deep space exploration, and yet Taes had insisted on a couple of lap pools for the gym. Captain’s prerogative. Awaking with that same single-mindedness, Taes had started her day by challenging Doctor Nelli to time trials in the pools. Worse, that decision had proven an act of hubris when Nelli had thoroughly trounced Taes, beating her in every race. In her moment of defeat, Taes’ competitiveness had risen up, and she’d proudly demanded rematches.

Sitting on the lip of one of the pools afterwards, Taes dangled her legs in the water, those demands long forgotten. She cinched a white robe over her swimsuit and laughed at Nelli’s retelling of their victory. Nelli’s plant-like Phylosian form remained wading in the pool, the water up to their midsection. Each of Nelli’s ten vines flapped vigorously –splashing the water’s surface– in an approximation of Taes’ swimming technique.

Shaking her bald head, Taes admitted, “I cherish this heartbeat and the sensation of the water, but I would be lying if I said my thoughts weren’t with the away team. Even when cramped in a makeshift duck blind, a prolonged observation assignment can inspire… such great clarity.”

Shaking their head-like bulb from side to side, Nelli said, “The wisdom of Starfleet protocol escapes me. Restraining a captain to the starship when the away team would benefit from her substantial experience? It impedes the away team’s success, no?”

Taes shrugged at Nelli. “I don’t follow that regulation in every circumstance. This time, we’re skin-deep in Borg territory. My place is undoubtedly on the bridge.”

The vocoder that synthesized Nelli’s auditory voice made a rumbling sound that Taes recognised as an expression of pause and consideration.

“The crew would benefit from visibility to you,” Nelli said in what sounded like a concession to Taes. Then Nelli went on to say, “You retreated from them for too many weeks in your resentment of Yuulik and your sorrow for thinking Kellin Rayco lost.”

Leaning back momentarily, Taes sputtered out an aghast cough.

“Ah, yes,” Taes said, suddenly stricken with shame. “Yes, yes, it hurts to hear that said out loud, but I suppose it’s fitting–“

“I was jealous of the closeness between the three of you,” Nelli said. Their artificially generated voice’s monotone was a stark contrast to such a vulnerable admission. “For a time, this one felt excluded from your senior staff. The deepest connection between Phylosians are formed biologically: a symbiotic exchange through mycorrhiza. Humanoids lack this ability. My first motivation for leaving my diplomatic corps, and joining Starfleet, was to discover that level of closeness in the outer galaxy.”

“There are other ways to connect,” Taes said, taking on a reassuring tone. Taes held her hands out, palms up. Nelli draped a vine over each palm, which bolstered Taes’ empathic sense of the intention behind Nelli’s universally-translated words.

Taes said, “I’ve read your scouting reports three times since you returned from the planet. I’ve gathered all I can from your xeno-anthropologic assessment of the sentient plant beings. They live in a warm and humid environment with frequent precipitation. They display a vast diversity of body plans, some with radial symmetric, others asymmetrical. You fit right in. I understand you found little evidence of them living together in permanent communities…

“Would you do me the favour,” Taes asked, “of telling me: what else? What minutia did you leave out of the reports because it seemed irrelevant?”

Nelli paused for a time and then replied, “Many of them sing spontaneously when the sun rises to its peak. Their song is composed from a cadence of ultrasonic popping sounds. My official report did not mention their song sounds like… the noise a phoretic analyser makes when you misalign the sample tray and try to activate the scanner.”

“Song of the phoretic analyser,” Taes exuberantly remarked and she gently released Nelli’s vines. “There’s a beauty in that.”

Nelli’s vocoder made a crackling sound, and then they said, “You have a wicked sense of humour.”

“I don’t believe I told a joke?” Taes said in mild confusion.

“Even funnier,” Nelli affirmed.

Compelled by her own curiosity, Taes asked, “How many different languages did you hear?”

“A dozen, mayhap,” Nelli said. “Many retreated from me in fear. When they fear, their aroma becomes sharp and fresh, almost antiseptic. Those who came near enough to communicate did so through the ultrasonic popping and transmitting electrical signals by touch. The signals from my touch were familiar enough to them –if a unique dialect– and the universal translator in my disguised vocoder adapted my speech.”

Taes asked, “You wrote about observing an easy harmony between the lifeforms and their environment, but not with one another?”

“My humble assumption, unfounded by science,” Nelli answered, “regards their cultures as being defined by independence. If they spoke Federation Standard, they would call themselves Solusians. From what I was told by the ones I met, even their family structures are small and impermanent.”

“A natural antithesis to collective,” Taes supposed.

Nelli’s eyestalks jerked in Taes’ direction when they said, “I asked about the Borg as obliquely as possible. None I spoke to had any understanding of technology or bipedal animals.”

“What a gift that would be,” Taes said, “to have no awareness of the Borg, no fear of assimilation.”

Bravo Fleet

Bravo Fleet