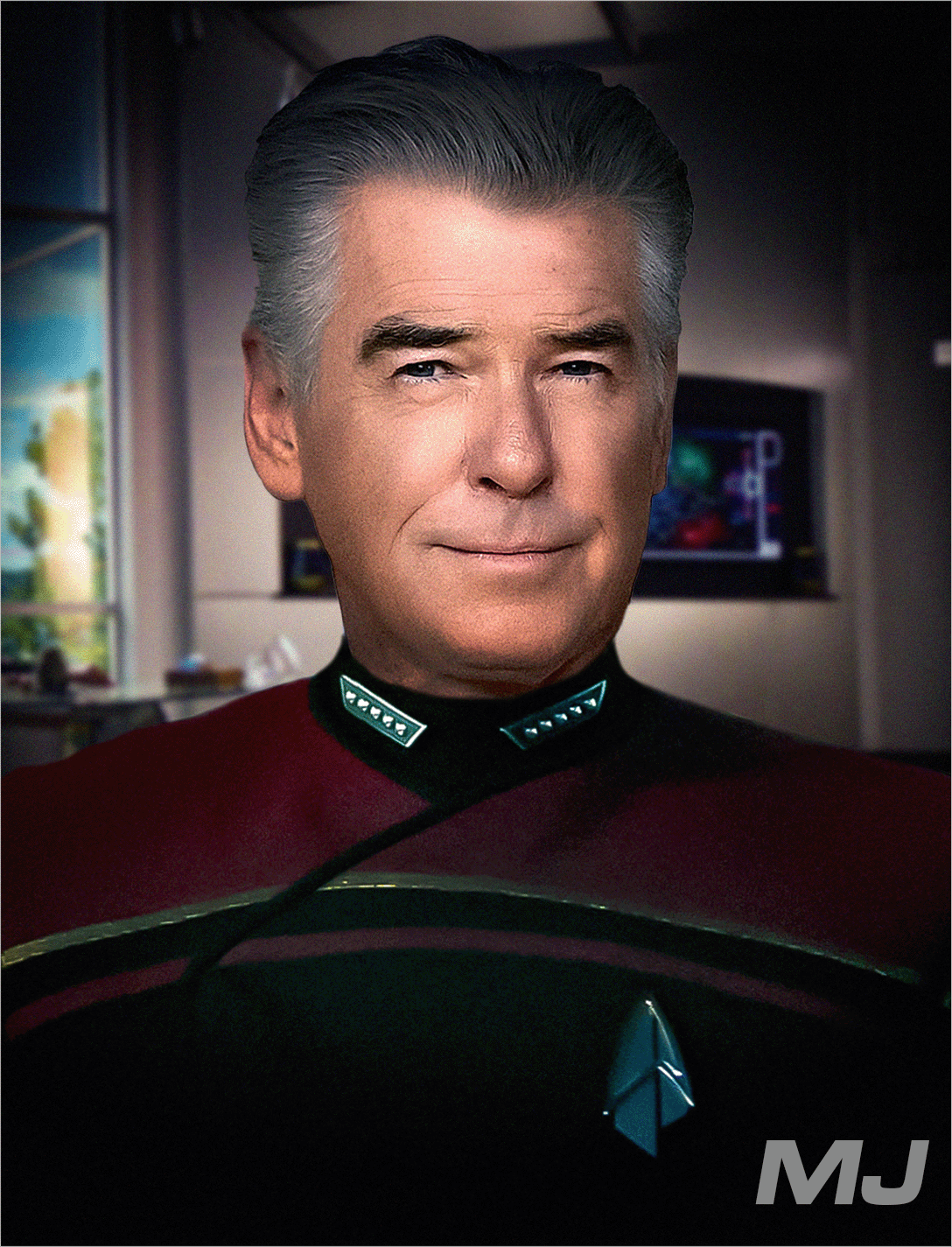

Captain’s Log, Stardate 77869.9

Given Captain Mek’s reports of a Devore Imperium warship in this sector, I… begrudgingly agreed with Commander Elbon’s recommendation that I remain aboard the Sarek while the away team conducts their first survey of Burleigh Minor. By all accounts, the Devore are expanding their borders aggressively to secure blood dilithium reefs for themselves.

Given the relative safety of scientific study, this was my first mission as captain when I did not join the away team personally.

I hate it.

Commander Elbon took the opportunity to stretch his legs. He did offer his personal assurance that all safety equipment has been installed appropriately. The away team has completed their initial survey of the dig site and I’m beaming down for myself to consider their preliminary reports and decide on a strategy for how to resume mining of the blood dilithium.

Coming from the bright lights and reflective surfaces of the USS Sarek, there was something alluring to Captain Taes about walking into the dark of the caverns beneath Burleigh Minor. Stepping out from a ring of pattern enhancer rods, Taes’ boots crunched across the rocky terrain. This ramiform cave system of irregular passages and large rooms was like a hundred other caves Taes had visited throughout her Starfleet career. She wouldn’t have liked to admit it out loud, but these caves felt more like home to her than her home colony of Nivoch or the Sarek both.

The passageway she crossed opened up into a particularly deep cave gallery and it looked to be where the crew from the California-class USS Palm Springs had set their mining intentions. The gallery was circled in deflector units, to ward off solar radiation, and portable work lights. An array of trans-sonic drills had been moved to one side of the cavern to make way for the Sarek‘s away team to begin their archaeological assessment with scanners only. Captain Taes had been afforded the final word on when digging would begin: either by the Sarek‘s archaeologists or by the Palm Springs‘ operations miners.

Taes slowly padded towards a gathering of science officers –Flavia, Yuulik and T’Kaal– and Doctor Nelli. Nelli waved one of the ten vines from their mid-section at Taes. This appeared to be a new human-like behaviour being exhibited by the flora-based Phylosian. Nelli’s leafy body was only vaguely humanoid in shape and when Taes had first started working with them, Nelli didn’t even reliably look at a person with their eye stalks while talking to them.

Using another vine, Nelli held out their tricorder and it projected a holographic image of a skeleton. As with most Starfleet technology, the sensor-generated image was intentionally antiseptic, with a cool blue glow rather than its visceral colour or texture. The skeleton, presumably buried beneath their own feet, appeared far more humanoid in nature than Nelli.

“Captain, direct your attention to these findings if you will,” Nelli said. The intonation from her vocoder device was largely monotone as always. “Our initial survey has identified at least five bodies in different locations across the cave system. Genetic sequence comparator scans confirm the skeletal remains were from the Kadi species. The time of death was… mayhap three hundred years ago?”

“Are you fecking kidding me?” interjected Captain Tommoso. Stomping towards Taes and Nelli, the Gallamite captain of the Palm Springs was an imposing figure even before he started shouting. His barrel chest was hardly contained in his red-shouldered Starfleet uniform, and his massive Gallamite skull was transparent enough to reveal every throbbing blood vessel in his head –not to mention his brain– as he began to exert himself.

“Our trans-sonic drills are all repaired,” Tommoso declared. “We’re equipped to continue mining and you lot want to talk about bones?!?”

In unison, Commanders Elbon Jakkelb and Kellin Rayco snapped their attention in Tommoso’s direction, with eyebrows raised and jaws set. Elbon fell into a quickstep behind Tommosso, demonstrating his well-worn practice at following in Taes’ footsteps as her executive officer. Kellin, meanwhile, snaked a different path across the cave to subtly use his body as a barricade between Tommoso and Taes. Kellin pretended to show a report on a PADD to Taes, likely as a facade for interposing himself between them.

With none of Elbon or Kellin’s tact, Flavia jammed her fists on the hips of her hunter-green jumpsuit. The Romulan Free State scientist sneered at Tommoso and she held her ground. As he came closer, his height meant Flavia had to crane her neck to look up at him. That awkward posture only made her expression sourer.

“So noisy, labourer,” Flavia spat at Tommoso. “You need to listen for once in your wasted life. You might actually learn something, even if only by accident.”

Tommoso sputtered wordlessly at the temerity of Taes’ Romulan chief science officer.

Lieutenant Sootrah Yuulik didn’t give Tommoso an inch of time or space to continue his incensed tirade. She waggled an accusatory finger through the holographic skeleton projected by Nelli’s tricorder.

“You’ve made an error, Nelli,” Yuulik said with the absolute conviction Taes would have expected to hear from the Kadi’s Supreme Abbott. “We found not one remnant of the Kadi’s ceremonial textiles, nor one broken basin from an ablutionary fountain. We would expect to find one or the other in every Kadi abode.”

Yuulik stretched out her arm to wave the translucent display of her own tricorder a couple of centimetres away from Nelli’s eye stalks.

“Alas, lieutenant,” Nelli intoned, “the error is rooted in you. The computer’s analysis only anticipated a seven percent margin of error. The remains are Kadi.”

“Tell her, ensign,” Yuulik ordered.

A couple of paces behind Yuulik, Ensign T’Kaal visibly winced at Yuulik’s words. If Taes wasn’t mistaken, the very pitch of Yuulik’s voice was causing T’Kaal to grind her teeth. It wasn’t the first time, or the hundredth time, Taes had witnessed a headache caused by Yuulik, but Taes had never before seen such a visceral reaction from the even-tempered Vulcan science officer.

T’Kaal responded by saying, “We identified scrap from a space-faring vessel, buried deep. Our metallurgical analysis identified a match in our library computer database. It’s Hirogen.” T’Kaal’s timbre was entirely formal, demonstrating none of the micro-expressions of discomfort that momentarily flashed on her face.

“We think there’s Hirogen armour down there too,” Flavia said, kicking at the ground with the heel of her boot. Fixing Captain Tommoso with a glare of naked disdain, Flavia added, “The remains of a Hirogen strike ship is what busted your precious drill, captain.”

“Could the Kadi have been trophies?” Taes asked, speaking her first thought out loud. “They were prey a Hirogen pack hunted for sport and brought back here as part of a collection?”

Flavia shook her head at Taes. “Tsk, tsk, tsk, captain. Objects in space are meaningless. The context they’re found in tells us the most. Besides, the object that’s absent matters as much as what’s there.”

Taes shot Flavia her finest impersonation of a bored expression. She raised a hand to chest level and made a circular gesture in the air with her wrist.

“Don’t keep me in suspense,” Taes said flatly. “What am I missing?”

“Tell her, doctor,” Flavia prompted, sounding troublingly similar to Yuulik.

Nelli advised, “We found no indication of Hirogen remains at this site.”

Taes took a sharp intake of breath. She crossed her arms over her abdomen and hugged herself tightly because it was going to hurt to say what she knew to be true.

“You’re right, Flavia,” Taes said. “We have to be mindful of how we conceptualise the alterity” –Taes looked to Captain Tommoso and she said it more simply– “the otherness of the Kadi. In all of Starfleet’s interactions with the Holy Goddess Mother’s Great Kadi State, their people have presented as deeply spiritual followers of total abstinence. However, that doesn’t have to mean they were the Hirogen’s prey. Maybe the Kadi hunted the Hirogen three hundred years ago?”

“Oh no,” Yuulik said, her bulbous eyes going wider at Taes. “I know that look. You’re about to tell us to stop.”

“She wouldn’t dare,” Flavia retorted.

Taes was already staring at Elbon. While Taes had been an archaeologist on and off throughout her career, Elbon had served as a diplomatic officer before joining Taes’ crew. Elbon nodded at Taes begrudgingly.

“We’re not the proprietors of the Kadi’s past,” Elbon explained. “Not even Starfleet’s noble curiosity gives us that right.”

Taes continued, “If we’re going to excavate a site of cultural heritage value to the Kadi, we need Kadi representatives on-site to review our plans and offer recommendations on mitigation strategies. We can’t dig up the remains and we can’t disturb the remains to dig up the dilithium.”

Flavia threw her hands in the air in a gesture of futile frustration. She groaned melodramatically and pressed her palms to her forehead.

And then Flavia said, “More condescending Starfleet moral relativism. All the beings in the universe are dirty youths compared to the pillars of virtue you are, huh?”

“Starfleet’s diplomatic relations with the Kadi,” Taes said, “has presented us with a culture that places strict restrictions on how the Kadi are exposed to medical procedures or stimuli that inflame the senses. They very well may have strong wishes about how the bodies of their dead are to be handled.”

Captain Tommoso didn’t wait this time. “Do you understand what you’re proposing, captain?”

“I do,” Taes said.

“I intend to file an objection to Captain Mek,” Tommoso said, referring to their task force commander.

“Please do,” Taes said.

“We need to dig up more of this blood dilithium,” Tommosso affirmed. “We need more scientific eyes on the stuff. If we don’t study it, we’ll never understand why it’s such a threat to the well-being of telepaths. If we’re not careful, by next year, half the starships in the galaxy could be fuelled by blood dilithium that undermines every telepathic species. Captain, if you won’t approve me mining here, then we have to move on. This close to chaotic space, there are dozens more planetoids, maybe hundreds more–“

“We can’t leave,” Taes insisted quietly. “We have to protect this excavation site and the Kadi remains from others who may come for the dilithium.”

Growling with frustration, Tomosso said, “We have members of both our crews who are in danger if we remain in orbit of a blood dilithium reef. Yourself especially.”

“I am aware,” Taes said; “Thank you.”

Tomosso blinked hard at Taes. The flicker of movement was almost indistinguishable given his transparent skin and skull. “You’re… aware?”

Taes stood taller and she said, “You’re permitted to return to your ship, captain. I don’t want to keep you from your objection.”

Tomosso didn’t say anything else before requesting a beam up to the USS Palm Springs. As if inspired by the storm off, Flavia tapped her own combadge and requested to be beamed up alone to the USS Sarek. Kellin started to protest Flavia leaving in the middle of a senior staff briefing, but Taes shushed him to let her go. It was only after Flavia dematerialised that Taes continued.

“Starfleet has never had much in the way of a dialogue with the Hirogen, much less diplomatic relations,” Taes said, “but we need to transport a representative of the Kadi to this dig site as swiftly as we can.”

Elbon breathed out a discouraging, “Huh.” He said, “There were reports of a group of humans being expelled from the Kadi homeworld over a month ago. The Holy College of Abbotts may not respond kindly to the Federation wanting to dig up Kadi graves.”

“Captain James McCallister of the USS Odyssey,” Taes countered, “passed through the Kadi homeworld on a goodwill mission recently; he dined with the Kadi’s Supreme Abbott. Starfleet is on good terms with the Kadi State.”

Elbon appeared to feed on Taes’ encouragement, nodding more hopefully at each statement.

“I’ve negotiated these types of agreements a dozen times,” Elbon said. “I’ll take the Orion-class runabout… What’s it called…?”

“Kalev,” Kellin chimed in.

“At the Kalev‘s top speed,” Elbon assessed, “I can get to the Kadi homeworld and back in a matter of days. Maybe a week.”

“I object,” Kellin said, far more firmly than Taes expected. She supposed Kellin was trying his lieutenant commander’s pips out for size. “You can’t defend yourself from a Devore warship in a runabout. They’re not only hunting for blood dilithium; they’re detaining passing ships and inspecting them for telepaths and then kidnapping them!”

“There was another report this morning,” Taes said soberly. “The USS Ulysses has missed two subspace check-ins with the Markonian Outpost. They’ve gone missing. Kellin’s right, the safety of the Kadi’s ambassador must be paramount.”

“See?” Kellin said to Elbon. He didn’t sound self-satisfied by the captain’s agreement like Yuulik might; he sounded protective. “You’re not going anywhere in a runabout.”

Taes nodded briskly at Elbon herself. “Take the Sarek‘s stardrive section instead.”

“The what?” Kellin asked.

“Captain Tommoso was right about one thing,” Taes said intently. “The blood dilithium is our mission: we need to understand where it comes from and how to make it safe to use in warp cores. I’ll separate the saucer section and remain in orbit of Burleigh Minor with the archaeological site. Elbon will command the stardrive section to parley with the Kadi so we can reach an agreement on how to mine the blood dilithium.”

“Wicked!” Yuulik interjected. “I want the mission pod.”

Bravo Fleet

Bravo Fleet