The Husk looked like the battlefield it had become, even in the Upper District. This time when Rourke turned away from the view from the balcony, he had not been looking upon the serene conditions of the former elites of Agarath. Below him were wrecked avenues and buildings, and among them the Remans and Romulans of the Lower Streets, whose habitations had been devastated by the Klingons, moving between the new shelters here.

‘It’s good of you to open the Upper District for all, Lady Zaviss,’ he said, throat tight. ‘And it was good of you to bring your guard down to reinforce…’

She didn’t have fancy drinks this time, sat on the edge of a sun lounger in another of those battered jumpsuits she’d been wearing when first he saw her. Now she looked up at him with cold eyes. ‘But you’re going to lecture me for the executions.’

Across the balcony, near the door to the building so he could stay in the shade from the Upper District’s false sun as much as possible, Korsk snorted. ‘It was the right damn thing to do.’

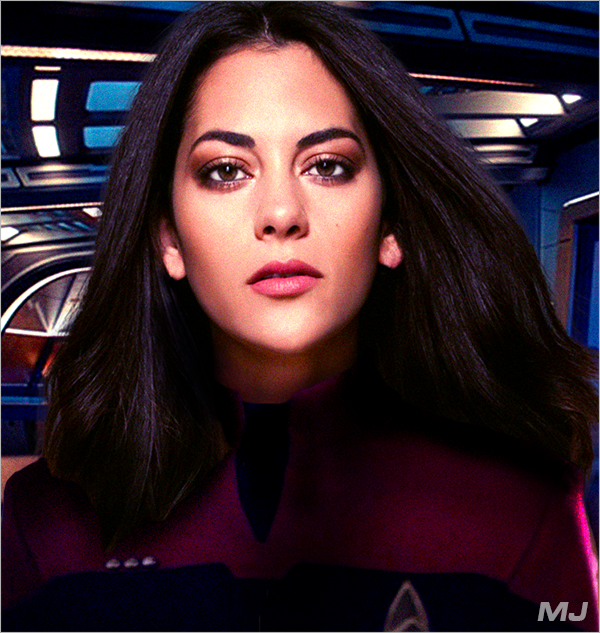

Rourke’s gaze flickered between the two of them, then to Kharth, leaning on the railing with her eyes shut. Exhausted though she had been when the dust had settled, asking her to come with him to the Husk had somehow made her more tired.

‘It was slaughter without due process,’ Rourke said carefully. ‘And I cannot support it.’

‘So, what?’ said Korsk. ‘You come this far, you bleed and fight and lose people for us, and now, because we did the right thing to defend ourselves – and your officers who’d have been overrun at the Crossroads – you’re going to turn your back on us?’

Zaviss lifted a hand. ‘He won’t. He just has to express his Starfleet disapproval.’

You think yourself a man of duty until your heart burns. Rourke swallowed. ‘If anything like this happens again, the Federation will find it untenable to support the new administration of Agarath.’

Another scoff from Korsk, but Zaviss nodded. ‘We did what we had to in a time of war. Now we hope to rebuild. You just looked out on the streets, Captain – did you miss how everyone is come together? Our backs were against a wall and we had to pick a side. But that meant we had to know everyone was on our side.’

‘If the Upper District can come to our help,’ rumbled Korsk, ‘and take out the trash on its own, maybe Hiran’s dream does happen.’

Rourke swallowed again, and did not say what he was thinking. Hiran’s opinion was immaterial now he was dead. ‘The two of you will work together for the new administration?’

They exchanged glances, and Zaviss gave a small shrug. ‘It seems fitting.’ She rose and regarded them. ‘I thank you for your work here at Agarath, Captain. I know there is more rebuilding to be done, but I understand from Governor Resak that the Romulan Republic has made offers of help, possibly membership. We will not need to be a burden on Starfleet for much longer.’

‘We’ll stick around to help with the handover, but, yes. Our orders are to let the Republic take over the relief work.’

Zaviss nodded and turned. ‘And you, Lieutenant. Agarath’s people owe you a debt.’ At Kharth’s confused frown, she smiled. ‘You commanded our forces in battle, convinced the Star Navy to work alongside us. You repelled all manner of our enemies. Thank you.’

Kharth shifted her feet uncomfortably. ‘It’s important you remember Relekor,’ she said awkwardly. ‘He died fighting to make sure we protected all people of Agarath.’

‘He was an idiot,’ said Korsk, but fondness had entered his voice. ‘But he was one of us. You’re one of us now, too.’

It’s funny, Rourke thought as they finished the meeting, how we change how we remember the dead. Then he thought of Graelin, of the body they’d recovered from the zenite mines, and he stopped thinking about that.

They left Zaviss and Korsk there, in the battered remains of the Upper Districts, stood with Romulans and Remans alike under its false sun to plan the future leadership of Agarath. And he knew that its path was not his to affect any more.

‘I don’t know,’ said Kharth when they stepped off Endeavour’s transporter pad after beaming back aboard, ‘if they’re going to work brilliantly together or kill each other. I’ve the bad feeling they’re both the same kind of nasty, and they’ve just realised it.’

‘Zaviss committed a war crime by any definition,’ Rourke grumbled. ‘But I’m damned if I know what we’re supposed to do about it.’

‘The Republic can deal with it.’ Then their eyes met. ‘I should get to Security, sir, there’s a lot to do with Juarez gone -’

‘I’ll write the letter to his folks,’ Rourke said abruptly. ‘I was there. I owe them that.’

‘He was my deputy, sir. My responsibility.’

‘I’m sorry. But give me a little more of your time, Lieutenant. Come to my ready room.’

It was a stiffer and more awkward trip by turbolift than he’d have liked, but the tension felt like it hung everywhere, at least, rather than from the old rift between them. They had their own thoughts and burdens, a sense of the cost of Agarath’s hard-won survival, and there was little appetite for chit-chat.

Rourke tried to not look at the communications station when they crossed the bridge. Lindgren had refused all offers of time off, pointing out she could rest when they left Agarath. She had not, to his knowledge, been down to see Graelin’s remains. That was probably for the best.

Valance was in the ready room already when they arrived. ‘Have you done it?’ she asked Rourke.

He tried to not frown. ‘We’ve had our last meeting with Zaviss and Korsk,’ he confirmed. ‘The Republic should arrive tomorrow. We do the handover. We get the hell out of here.’

‘I think our time would be best-used helping Agarath’s military assets in the meantime,’ said Valance. ‘We’ve offered basic relief, but we can help their defences much better and quicker than the Republic can.’

‘Agreed.’ Rourke turned to Kharth. ‘Where do you think we should start? The ships or the platforms?’

Kharth frowned a little. ‘I think the ships, but… you two know all of this. Is this what you asked me up here, for?’

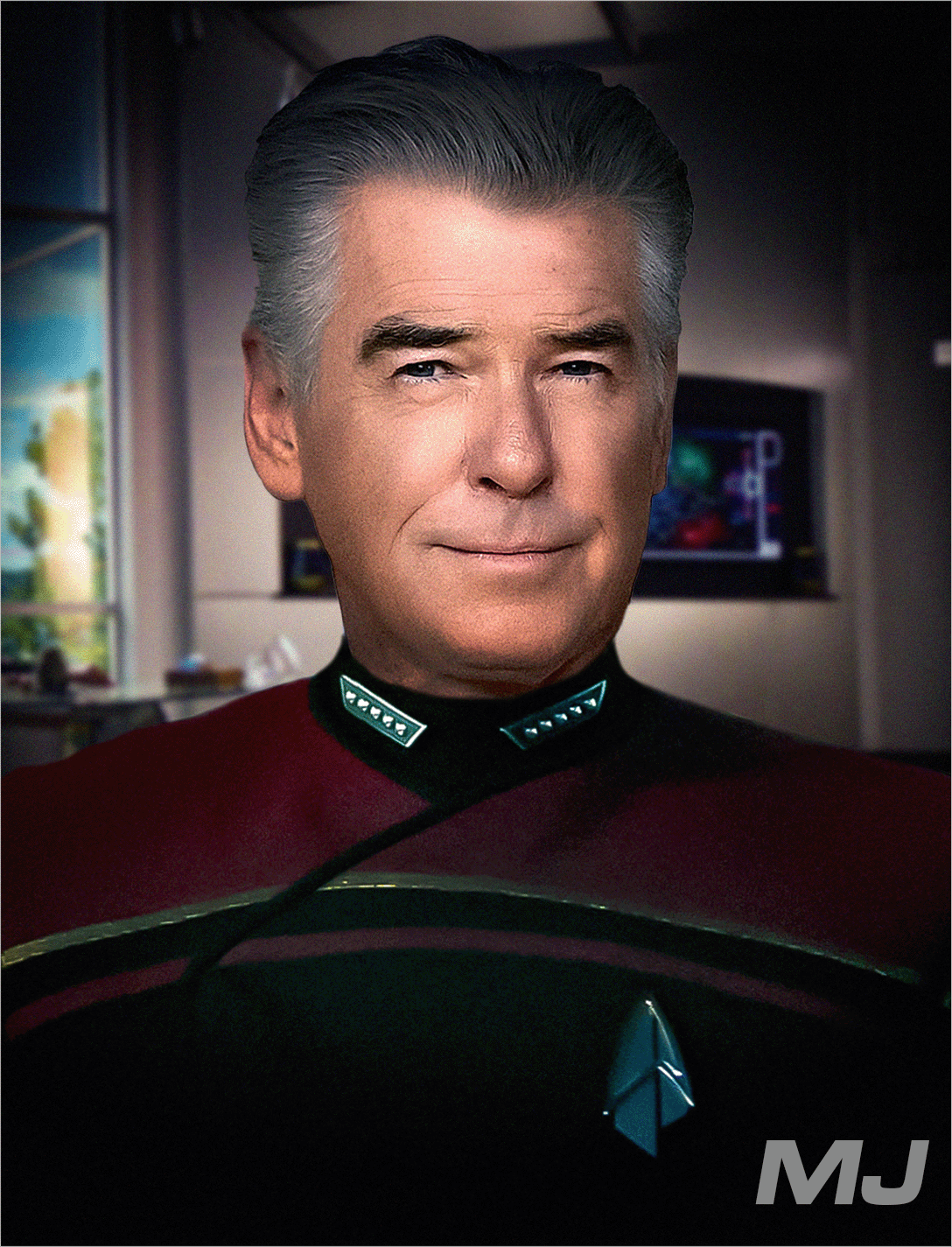

‘Sure,’ said Rourke, walking around his desk and pulling open a drawer. ‘See, I had more than one conversation with Command. Obviously we talked Agarath, and the mission, and Lotharn, and K’Var… all of that. But we also talked Endeavour.’ He pulled out a small box and tossed it to her. ‘And how I need a new second officer.’

Kharth caught the box more out of reflex, then stared at it without opening. ‘Sir…’

‘I could list all the things you’ve done in the last week alone to justify recognition. We can hold a party about this later, but I want to get to work now, and I think you do, too.’ Rourke straightened. ‘It’s not just about your skill. There’s nobody else in the command staff who gives both of us a better, different, and more challenging perspective.’

Kharth glanced up at Valance, and her expression creased. ‘You’re not against this?’

Valance shrugged. ‘I had opinions,’ she said. ‘I expect you and I will have more… opinions, Lieutenant Commander.’

‘Oh yeah,’ said Rourke, ‘that part’s non-negotiable. You get that just because you deserve it. But you can turn down the title bump and I get, I don’t know, Nate in to be my yes-man and serve me tea.’

‘Beckett would not be that cooperative,’ Kharth mused, but at last she snapped the small box open to show the small, shining pip, and stared.

Rourke softened. ‘I heard what you heard in Zaviss and Korsk’s gratitude: that you have a place on Agarath if you ever need it. I want to make something abundantly clear to you, Saeihr: this is your home, too. Not just Endeavour. You fight harder than anyone I know to do the right thing for the underdog, and that’s what we should be about. Don’t ever think you’re on the fringes of Starfleet. You’re Starfleet to the bloody core. When your back’s against a wall, you don’t forget who you are.’ He felt Valance’s gaze flicker to him, and wondered if she heard the echo of Lotharn’s voice in his words.

But Kharth had pulled out the pip and broken Valance’s attention, and looked up with a deep breath. ‘I accept, sir.’

He beamed. ‘Then congratulations, Lieutenant Commander Kharth.’

When Kharth left, he gave Valance a cautious look. ‘For the record, you’ve had your chance to object to this.’

Valance shrugged. ‘Kharth and I these days have… an accord.’ But her expression soured. ‘Replacing Graelin at Science will be harder.’

‘You think Veldman isn’t ready?’

‘Veldman just got another research project with the Daystrom Institute. I think she’s happy where she is, she’s a scientist first. We can keep her in the position temporarily, but I think we’ll need someone sending in.’

They exchanged glances, but before Rourke could decide whether to venture his opinion, there was a chirrup at his console.

‘Lindgren to Rourke. Captain, there’s a high-priority subspace message for you. It’s from the House of K’Var.’

Valance winced. ‘Should I go?’

He shook his head, and sat down warily before flipping his screen on. Before him sat the stern-faced figure of Torkath, son of K’Var.

‘Matthew.’

Rourke sighed. ‘You didn’t come for pleasantries, Torkath. I expect your warriors have returned by now.’

‘Desperate with their apologies, begging for my father’s mercy, and blaming everything on Dakor.’ Torkath rolled his shoulders. ‘Whose arms and armour they did not recover.’

‘They didn’t.’ Rourke clasped his hands to not fidget. ‘I have them.’

‘His first mate says he sought you out for battle. I had not known his acrimony against you was so deep, but it does not shock me.’ Their eyes met. ‘What happened?’

‘He wanted Agarath’s wealth and resources, and to use them to leverage his influence in the House.’

‘I do not need you to explain the politics to me, Matthew. I understand why my brother acted, far better than you do.’ The tension in Torkath’s voice put a chill through him. He had not looked forward to this conversation, and it seemed he had been right to be apprehensive. ‘I am asking how he died.’

His mouth was dry. ‘I killed him.’

Torkath shut his eyes and exhaled slowly. ‘Explain.’

‘He’d attacked me and my party. And he had a knife to the throat of – of one of my people. Someone I’m responsible for, someone it’s a great honour to be responsible for -’

‘Someone, by your tone, important to you.’ Torkath bowed his head. ‘We swore oaths to one another, Matthew.’

‘I swore oaths to you, not to Dakor or your House -’

‘And there was no other way?’ He sounded hurt. That was the worst thing, Rourke thought; this was no bluster of Klingon honour and broken vows, of the complex series of oaths intertwining so tightly something snapped. This was nothing more complicated than pain, and pain he’d caused.

‘If I could have found another way,’ Rourke said as gently as he could, ‘I would have taken it.’

Torkath looked away, gaze going distant when he opened his eyes. ‘So you made your choices.’

‘I did what I had to -’

‘That was my brother, Rourke.’ Torkath’s eyes snapped back to him, colder than Rourke had ever seen them. ‘K’Var will not forget.’

‘Torkath -’

But the screen went dead, and in the silence that followed, Rourke could feel the sick sense of the violence of the past days catching up with him. He bowed his head.

‘Dakor put you in an untenable position,’ said Valance at length, and he’d almost forgotten she was there.

Rourke drew a raking breath. ‘I’m not sure he did. Every decision I saw would have put Hale in astonishing danger anyway. I chose the astonishing danger that ended it quickly – and killed Dakor.’

‘I remember what happened to us last year,’ she said delicately, ‘in the Azure Nebula.’ He was silent, brow furrowing as he tried to find the connection. ‘Where I saw what happened on the Firebrand.’

Rourke worked his jaw and looked up. ‘Forgive me, Commander, but I don’t see the connection.’

‘You don’t?’ Valance looked sincerely confused. ‘You don’t see the link between Dakor holding a blade to Hale’s throat, and a Nausicaan holding your crew hostage on his bridge? I don’t know exactly how the phenomenon worked, but every other time, we saw how key points in our lives – our trauma – could have gone differently. Except for the Firebrand. We just saw a dozen realities where nothing you did could possibly save them.’

He tore his gaze away, because keeping it on her burned. They had barely talked about that experience, the first to truly bond them; how they, as rivals resenting working together, had been forced to see each other’s darkest times. ‘I hadn’t thought about it like that.’

‘I know this sounds obvious. But you should talk to Carraway, sir. Because I can’t imagine how seeing someone you’re responsible for – care about – being held hostage in front of you could be anything other than, well… horribly triggering.’

Rourke had to keep his gaze on the window, on the view of Agarath’s asteroid belt beyond Endeavour’s hull. He had not stopped in days, he realised; not properly, not in a way where he could let himself think or feel or do anything but act, act, act. He was not about to start, yet, but with Valance’s words he could begin to feel the edges of what was to come.

It tasted of bitter, ancient adrenaline, rotten inside him and still churning when he wanted it least. You’re a man of duty until your heart burns, he remembered again. And then he remembered that when he’d lost everything on the Firebrand, he hadn’t been anything at all, not for a long time. Just his pain.

At length he looked up, meeting her gaze wearily. ‘Agarath should feel more like a victory than it is.’

‘Victories aren’t usually as clear as we’d want them to be. This one was quite good,’ Valance said with surprising gentleness.

‘A political wedge driven between us and one of our closest border houses in the Klingon Empire, a new administration in Agarath bathed in the blood of innocents -’

‘Bathed in the blood of an extrajudicial murder. Innocents is perhaps a step too far. And Dakor drove that wedge in. You didn’t.’

He opened his mouth, and realised he had nothing to say that wouldn’t sound like he was demanding her validation, voicing the criticisms of Lotharn and Graelin and asking her to refute them for him. And he was, Rourke realised, very tired.

She tilted her head in his silence, and, as if reading his mind very badly, said, ‘I know you and Graelin served together a while…’

‘Graelin was an arsehole.’ Rourke swallowed. The least he could do was obey the man’s final wishes and not turn him into something in death. ‘We fundamentally disagreed on pretty much everything. He was a smug weasel.’ He scrubbed his face with his hands. ‘He was a good officer. I don’t know if he was a good man, but he died protecting hundreds of people. I have no idea if I’ll miss him.’ With a sigh, he dragged his hands down his face. ‘This campaign gave us strange bedfellows indeed.’

‘For what it’s worth, sir, I think it speaks well of you how you handled the Romulan Star Empire.’ Valance’s voice was still softer than usual. ‘Your tactics forced Lotharn quickly to the table. And when things went sideways, you made an alliance with him. Those two things defined our victory more than anything else.’

‘Maybe.’ Another sigh, and he looked up at her with an apologetic smile. ‘I’m very tired, Commander.’

‘Of course, sir.’ Valance inclined her head. ‘Get some rest.’

He closed his eyes once she was gone, slumped back in his chair and sat doing nothing more than listening to, feeling, the hum of the starship around him. His starship, whose crew he was responsible for above and beyond anything else. Even Petrias Graelin, whom he’d hated. Even Sophia Hale, who was not his crew, and yet to whom he had perhaps an even greater obligation.

When he tapped his combadge it was in a short, sharp move, as if he’d lose his nerve if he didn’t do it suddenly. ‘Rourke to Carraway.’

A beat. ‘Carraway here, Captain. Would you like me to make some time for you?’ Greg Carraway spoke easily, cordially – gentle without being pampering.

He gave a wry chuckle. ‘What gave me away, Counsellor? But not yet. Not until we leave the system. I’d just…’ The chuckle died in his throat, and Rourke gave a difficult swallow. ‘If you could familiarise yourself again with my records from Starfleet Medical, 2397. I think… I think that’d be helpful.’ Now his eyes opened, and he scowled at the bulkhead. ‘I think I’d find it helpful.’

‘I understand, Captain. I’ll slot you in as soon as I can once we’re underway, and get some reading done. Feel free to stop by for some tea in the meantime. Carraway out.’

Rourke knew the hidden meanings; Carraway wouldn’t just slot him in, he’d clear his schedule and if necessary drag Rourke down for counselling the moment he knew the captain was out of excuses. But he wouldn’t frame it like that until he had to.

He checked his console. The Republic relief team was six hours out. Even a few hours’ rest between now and then would be better than nothing.

And still his feet did not take him to his quarters. Nor to the Round Table, or the Safe House, or off the ship. After leaving his ready room, leaving the bridge where he again did not look at Lindgren if he could help it, he found himself sooner than he’d expected at a destination that did not, really, surprise him as much as it could have.

When Hale opened the door to her quarters, her gaze was unsurprised. ‘Matthew.’

Her name caught on his tongue, because he didn’t know if he wanted to speak to her as an equal or keep the barriers of formality between them. They had not talked properly since before the Romulan strike force’s arrival; since their argument on the fate of Agarath. ‘I know you’re just back from the surface,’ he said instead, voice grating. ‘But I only want a moment, if you have it.’

She looked tired, and still ushered him in without hesitation. She wore the usual formal-wear that acted as part of her shield in negotiations, the comfortable Federation respectability that made her look in control of herself, and representing an offer of a better future. But the jacket was off, the collar loose, and without anyone she needed to fool, her smile did not quite meet her eyes.

‘I don’t know if I can reassure you much about Zaviss and Korsk,’ she admitted. ‘They are, at least, cooperating. I think the Republic and Psi Velorum now exerting influence may help the situation…’

‘I didn’t come here to talk about Zaviss and Korsk,’ he said quietly, clasping his hands behind his back as his gaze swept around her dim-lit quarters. With the diplomatic suites and her offices, he realised she had so many places to bring official guests that there were no airs and graces here, no professional deliberation to the decor. It was spartan in a way that at a glance looked minimalist, and only when he truly looked now did he realise was instead quite bare.

He turned to her. ‘I wanted to talk about Petrarch.’

Hale hesitated. ‘I’m truly sorry about Juarez. Everyone liked him.’

‘Thank you.’ Juarez had served on the old Endeavour under Leo MacCallister, was one of their veterans. He would be heartily missed and hard to replace. Still, Rourke bit his lip. ‘I meant I wanted to talk about what I did. Shooting Dakor.’

Now her expression shifted for the mask to come down. ‘I’m not really sure I’m qualified to assess your decision -’

‘It was your life on the line. That makes you qualified.’ He drew a slow breath. ‘And I broke pretty much every single standard of regulation, guidance, or even… good judgement in what I did. The fact that it paid off is no excuse.’

Her brow furrowed a hint. ‘I agree,’ Hale said eventually. ‘But I’m not sure I would prefer to have been abducted by renegade Klingons.’

‘The House of K’Var couldn’t -’

‘It’s been a long time since my life was in danger like that. But I remember what it is like, and I remember that there are worse things than death.’

Her gaze did not waver, and he found his mind racing even as he tasted that bitter, rotten adrenaline again. ‘You were in the shuttle crash that killed your husband and son,’ he realised in a hushed voice. And he remembered how she had barely blinked on Petrarch in the face of death, had been shaken but quick to recover after his irresponsible phaser shot, and he opened his mouth but couldn’t quite find the words to form the question.

Did you care that much if I hit you or not?

‘I trust you,’ she said instead of responding to his point. ‘I may have called you a – a problem-solver, Matthew, but sometimes there are problems and sometimes they need solving. And I trust you to do that.’

‘I’m not…’ It felt like the deck was slipping away from under him. ‘I am not cavalier with your life, Sophia. I couldn’t – the idea of letting Dakor take you away was, was unimaginable.’ At last the burning was coming again, but it was with a more desperate fear at her reaction than the blazing guilt for his own actions that he’d expected.

‘I know.’ But he couldn’t find comfort in her soft smile, or how she advanced on him to bring a hand to his arm. ‘And I appreciate that you care that much. I truly do. I may have had better things to worry about, but I’ve spent days despising how we argued. And I’m sorry for what I said.’

He didn’t know if she was trying to appease him to make the conversation go away, or if this seeming indifference dripping from her was sincere, and he didn’t know which of the two he hated more. And still he tasted his own bitter failures, and knew they were blinding him to what was real, to what others needed, and try as he could, he couldn’t force them away so he could see clearly or say whatever would help.

So instead he said, ‘You know I’ve trusted you with Agarath, right? That I never thought you were working against me. But you’re the only person aboard I can have these conversations with – these disagreements with…’

‘And that’s a double-edged sword,’ she finished for him, again with that enigmatic smile that couldn’t bring comfort. ‘Because you’re master of this ship, and if I am to be your equal, sometimes that means you are not master of its fate.’ She paused, and her hand fell from his arm. ‘We’ve done good work here, Matthew. If Zaviss hadn’t been motivated to help in the battle, I think she and Korsk wouldn’t be cooperating now. However difficult that is, it is what Agarath needs above anything else – unity.’ Now the sadness entering her smile felt more sincere. ‘I think that, for once, I’m the cynic here. Because unity and agreements dipped in blood are regrettably common in diplomacy, and something we must live with.’

‘I think everything gets dipped in blood from time to time,’ Rourke found himself murmuring. ‘And still we have to live.’

It had taken him a long time to learn that lesson. Through years of counselling, years of licking his wounds; through coming to Endeavour and finding purpose and drive again. It was terrifying how quickly those wounds could reopen, how easily that blood could run anew, and by now Matthew Rourke knew that staunching the bleeding was not something he did on his own. Just as Agarath would not be left alone to staunch its bleeding; just as Endeavour had carried them through their darkest days and brought them to a point where they could be helped by others.

‘Still we have to live,’ Sophia Hale repeated, but the echo was in her voice as much as her words. Because sometimes the blood took years to wash away, and sometimes it never did.

Bravo Fleet

Bravo Fleet