‘Beneath a sky of pixelated stars,

We dance through constellations from afar…’

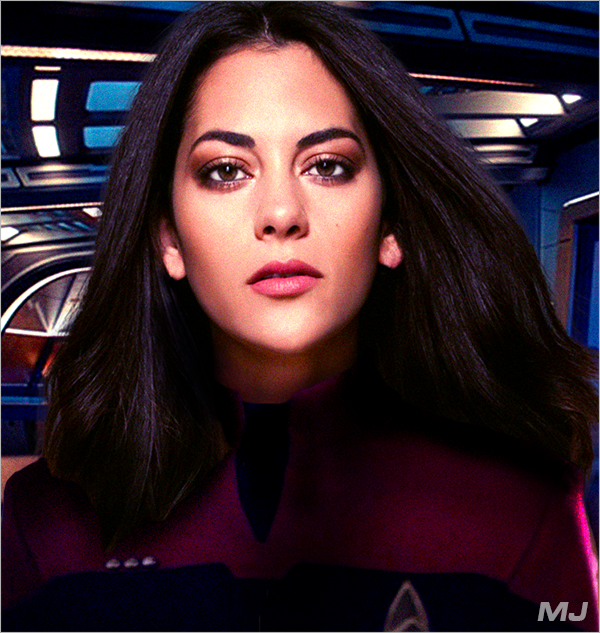

The refuelling station hung so low in the Petrion-7HG VII’s orbit that the morning sun had to break through the gas giant’s atmosphere before it flooded through the viewport. Cascading through the gases, it rendered them bronze and gold instead of the murky mud of night, and Thawn had to tilt her screen away so she could read her work through the glare. She could have brought the blind down, but she didn’t want to block the sun out from the grimy processing control room that had been her effective office the last few days. Thudding, pulsing, cheerful music had helped her through the dark, but now, at last, it was joined by sunlight.

‘Point two percent,’ she muttered as she read the findings. Then she shrugged. ‘We can do better.’ She reached for a button on the controls, turning her music down before she hit the comms. ‘Thawn to Jerevok. Are you seeing what I’m seeing?’

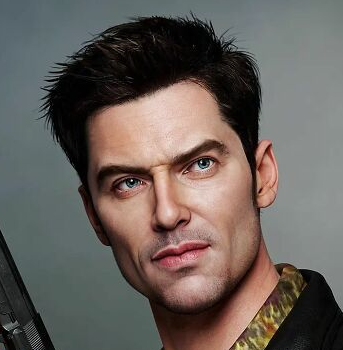

‘You forget we don’t have Starfleet-level networking in here, don’t you,’ came the Romulan man’s immediate, dry response. ‘I’ll see your readings in about ten minutes.’

‘That’s an exaggeration,’ Thawn blustered. ‘Anyway, I think that I was right -’

‘I’m astonished.’

‘And,’ she pressed on, cheeks flushing, ‘if we reinforce the secondary power coils on section 17, we can raise the intake flow by a few percent.’

‘You mean if I crawl down there and replace each panel by hand.’

Thawn blinked. ‘I’ll do it,’ she said, already reaching for the jacket on the back of her chair. ‘I’ll need to head down to the Starfall and replicate the parts -’

‘No, no, you need the exact measurements first. Besides, I want you to owe me so you replicate me more blue leaf tea.’

She bit her lip. ‘I think I owe you already for fixing that wave surfer on Armitor last week…’

‘That was pleasure. This is business. Besides, the work teams couldn’t see you flapping in the surf that pathetically and still listen to you, and I want you to leave me with a lot of blue leaf when you move on, anyway.’

Thawn gave a light laugh. ‘You have a deal. Check-in in thirty.’ She turned her music back up.

‘Stardust serenade, our hearts aglow,

In the cyber-void, our love will grow…’

After fifteen minutes, a shadow swung across the viewport to block out the sun, but Thawn ignored it, and it passed. Ships of the Khalagu came and went at Petrion all the time. It was their primary refuelling depot in the whole of the Synnef Nebula, and however far the itinerant fleet wandered, or individual ships went about their business, sooner or later, they all came back here.

It had been the runabout’s first stop at their expedition’s start five weeks ago. It was the best place to catch up with the main Khalagu fleet, and while Beckett had charmed locals who didn’t want to be charmed, Thawn’s mind had already turned to how to run this operation more efficiently. Initially, the Khalagu had been more prepared to listen to Beckett’s mouth than let her touch their equipment. They’d kept the first week or so of the trip to what now felt like a diplomatic veneer, letting their runabout fly alongside the main fleet and hold ship tours to meet captains and crews before stopping off at one of the Khalagu’s surface ports on Namalbu, with its endless beaches and nebula-stained skies.

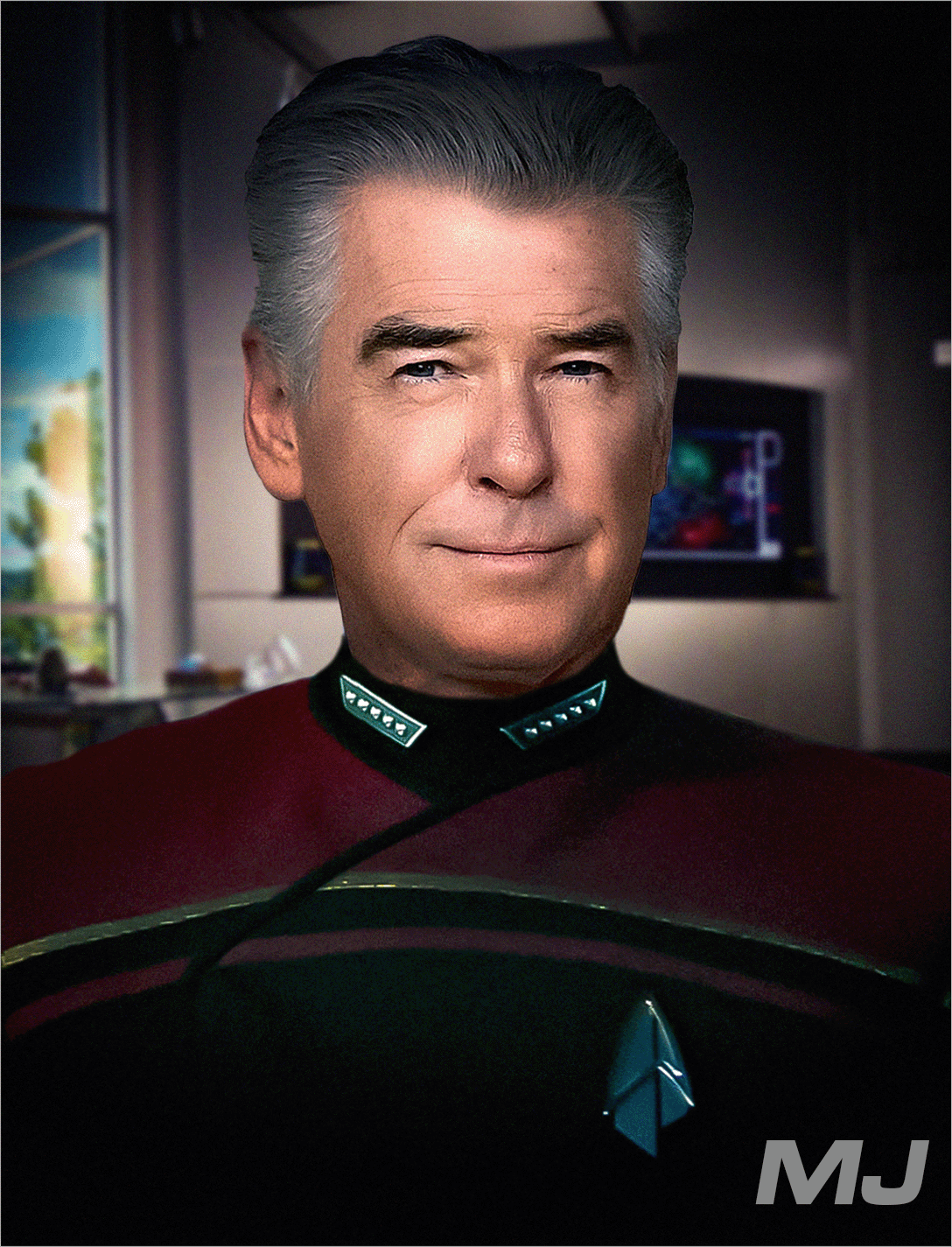

‘Why don’t you just stay here?’ Beckett had asked Narien as they contrasted white sand underfoot with drinks that tasted like they’d come from an engine sill. ‘It’s beautiful.’

Narien had looked from the beach-front structures – harsh, metal blocks built from fallen ships and scrounged metal – to the gentle waves and bowing purple trees, then up to the twin suns in the rippling skies. ‘If we stay in one place, they know where to find us.’

Neither of them asked who they were. The Khalagu were the unwanted dregs of Romulan society that-was, squatting on the border of the Republic and the Federation, wedged into the corners of space where the rejected vied for room or influence. Namalbu might be like a paradise, but it made them a target if it was anything other than a small resupply hub.

Thawn had been bored out of her mind by then, forbidden from working, from being useful when she could see a hundred ways to get her hands dirty. She’d slipped off to the communications control bunker on Namalbu’s surface and been halfway through studying how they masked their comms when Jerevok had found her. He couldn’t so much as begin a challenge or chastisement before she’d made three recommendations on how they could better mask their presence.

Beckett had been incensed when he’d found out. She’d put the whole expedition in jeopardy, he’d insisted. Had she been found by a different engineer to Jerevok, who it turned out had been exiled for his Reunification sympathies, Beckett might have been right. As it was, she’d been able to tilt her nose up and point out that they were no use being paraded through Khalagu space like strange royalty. They were there to make connections. This was how she made connections.

‘By pissing people off until they give in and let you have your own way?’ he’d retorted.

But now she could give a smug smile and say, ‘It worked on you,’ and rather than enter a fresh wave of endless argument, he kissed her to shut her up.

More importantly, Jerevok had all but press-ganged her into the Khalagu fleet’s engineering team, and by the end of week two, she’d made more progress ingratiating them with their host through her work than she suspected Beckett could have charmed in two months. On this return trip to Petrion, she’d been intent on making the most of it.

‘Through digital galaxies, we’ll navigate,

In this stardust serenade, we celebrate…’

‘What the hell is this racket?’

She hadn’t realised how high she’d turned the volume until she caught Beckett straining to be heard over it, the thudding bass masking his entrance to the room. She cut the music and turned, but refused to let any shame show as she looked him dead in the eye. ‘Tinker Starling. Stardust Serenade.’

‘You were listening to Baccharali yesterday,’ Beckett whined. They’d both given up on uniforms early on, dressed in rough-and-ready civilian garb. The Khalagu didn’t keep their ships especially warm, so he’d started to live in his leather jacket a little more than she liked. ‘How can one woman’s taste go from fine art to fine trash so fast?’

‘I like Speedwave in the morning,’ she said airily, tilting her nose. But he didn’t look like he was squaring up for them to argue about music choice, and there was a case under his arm. ‘What’s that? What’s wrong?’

‘I don’t know,’ he admitted, and advanced to put the case down on the central control table. ‘Narien just came in from Sot Thryfar. Said he’d picked something up he wanted us to see.

‘Us? This isn’t you two geeking out about more old Romulan archival pieces he’s picked up?’

Beckett shook his head. ‘He said he hasn’t opened it, that a friend double-checked he has “Starfleet contacts” and asked him to get it to them.’ He ran his fingers over the case, checking the seal conditions, checking the latch. It looked to Thawn’s eyes like an unremarkable containment case, sturdy to protect anything inside and locked solid to fend off light fingers, but nothing special.

She smacked his hand away as his fingers touched the latch and pulled out her tricorder. ‘One step at a time.’ But after a moment, she shook her head. ‘I’m just picking up a tritanium alloy over a layer of duranium composite, and I think there are micro-tritanium shells on the interior – without power signatures, this could be anything.’

‘I appreciate you making sure I don’t get my fingers blown off,’ Beckett said amiably, and popped the lid.

That was the difference, came Thawn’s thoughts, hollow and echoing and as if they had completely detached from her body the moment the lid was raised, between scans and eyes. Scans could tell her there was some device inside, tell her the exact thickness of the tritanium housing and duranium layer, give her details she couldn’t possibly identify for herself.

For herself, she could see the jagged shape of the device itself. The deep black of the housing. The dull green sheen of the circuitry running across it. For herself, she could recognise the impossible.

Beckett’s breath caught with a hint of a soft, strangled sound. ‘Is that what I think it is?’

Thawn stared for another moment. Then she reached to slam the case shut. ‘We’ve got to go.’

‘Go…’ He was still stunned, reeling.

‘Back to Endeavour. To Gateway.’ She turned and lifted a hand to his cheek. You’re not there. It’s not Frontier Day. Come here. Come back to me.

Whether her touch was enough or if, in her roiling fear, she’d reached out more with her mind than she’d intended, he blinked, and the clouds over his eyes faded. Beckett straightened. ‘You’re right. Shit. They’ve got to know. Because least bad case scenario…’

‘Least bad case scenario,’ said Thawn with a levelness she didn’t feel, ‘is that someone’s shipping Borg tech through Sot Thryfar.’

And neither of them wanted to voice the worst-case scenario.

Bravo Fleet

Bravo Fleet