The two men look like mountains, their shoulders sit higher than Uncle Tos and he has to stoop to get in the door when he comes to visit. Mother tells him to ‘watch his head’ but it never helps, we always laugh as he knocks his big rusty forehead on the lintel before stooping so low he could smell the earthworms. Tos always pretends he’s inspecting the floor for dirt. ‘You’ll not find a mark upon my floor chucka’. The little one she calls him, and we laugh. It has become a ritual of sorts, much like everything else we do. Everyone tells me I favour my father’s blood in my stature, all his kin were tall apparently. ‘Giants’ my mother muses over the pestle, smiling when she speaks of them, ‘of both heart and body.’ She told me it had been a whirlwind romance, that he had charmed her with tulkik roots carved in her likeness and giant comanch fish, their golden scales wrestled at the delta’s end where the snaking green river becomes the unspeakably vast blue ocean. Rumour was that he had presented my grandsire with a chest full of Talaxian silks and Hirogen blades scavenged from the marshes, cloth to dress his daughter and blades to guard her, a fine dowry for a Maje’s daughter. Of all my forebears only Tos remains in the village now, the others taken back to the sloppy ground or lifted to the search, leaping between shadows of the screeching sun.

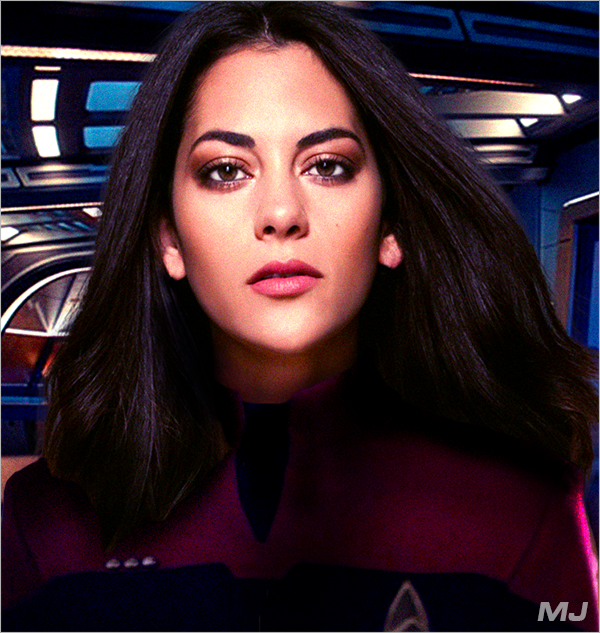

The nearest one is looking in my direction, I freeze to stone, but his eye wanders onwards. He is the most like me but with mottled grey skin like the idle moon that rolls in the sky. And silky black hair swept back on his head over pointed ears. Strange. But I see a familiarity in his heavy brow and lurking in the secret pools behind his eyes, I have seen it barely held in the visage of my uncle and I glimpsed in my father on the day he departed for the search. Anger. Violence.

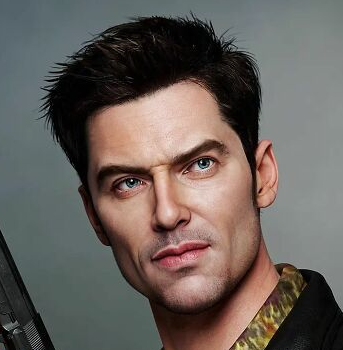

The other one is even stranger, his skin as blue as the beetles that crawl on the banks, rich and deep as the ocean, he looks at any moment like he might melt away into the water itself and slip out to the river mouth. I look at my own arms, imagining their copper tones turned blue and I shudder into the soles of my feet, such things are the visions of nightmares and fearful stories around the smouldering fire. Most worrying is his lack of hair, smooth head with no crest of hair. ‘Never trust a hairless hunter’ my great-grandmother had told me as she rocked on her chair, smoking her grisha root; but her mind was addled by time and root both, even my mother said it before she passed. Rumour had been she had seen the days of the Trabe, that she had witnessed the revolution of the Jal Sankur as he led us out into the deep aboard the ships of our oppressors. I asked her once about it, whether Jal had looked been tall like me, but she hushed me at her knee and told me only of days in waterless lands, traded between Ogla and Nistrim and Relora. Addled.

The wreck behind them is beginning to whine again, a great churning and gnashing of metal against metal. They seem unbothered, perhaps they are deaf to all but each other. The blue one laughs as he reaches to touch the other man. My ears are already protesting being this close to the wreck, I hear my mother’s warning, cutting through the cacophony that beats at my eardrums. ‘The wrecks are no place for a child, there is nothing left there that would interest you.’ I hate when she calls me a child. I am almost 13 anniversaries, if we were still aboard the ships I would be a warrior like my forefathers. I cried in anger at her once, screeching that I would have been a warrior if she hadn’t been stuck here. She spat at my feet and told me I was a fool and I saw it in her eyes too. Old violence and anger, a deeper heritage than we would admit.

The sound from the wreck eases, as from its high peak another yellow star emerges into the night sky. The two mountains are distracted, chattering in unfamiliar tongues as they smile and laugh. Now is my chance to sneak into the star machine. I pick my way through the reeds and hold my breath as I brush their stems with my lanky arms, fearful they will look and spy my hiding place. But they are lost in their low-toned chittering and I slip into the wreck’s open wound, the ripples of my footsteps pinging on the dark metal that rises from the murky water.

The two beings within are stranger still, I can see them clearly from my hiding place in the ducting. My father had always said my long arms and slight body would be a blessing. Two aliens work in the room below, huddled around their little light sources, I make note that their night sight might be bad, a useful thing to remember if I have to run. The nearest one is like a great feathered bird, it chatters and clucks with a beak that could puncture a searcher ship’s skin, curving like the meat hooks in mother’s pantry, one long scar running down its pale blue length till it ends at the cruel looking tip. I shudder as it summons the memory of a close encounter with a Ghona bird, the great hunting raptor had taken a fancy to me when I strayed too close to its nest. I can feel the heat of its breath even now, the deafening crunch as its beak snapped together, the cold warmth of my fear running down my leg. The bird-like one throws its head back and clacks its beak together in rapid succession, a strange staccato laughter echoing along the metallic corridor. It itches my ears but the other one seems unphased, are all these creatures as deaf as each other?

I cannot see anything I would call ears on the other one, only small holes in its pale pink skin. It’s ugly by any estimation, with flat hairless skin like the blue one outside but scaled and rough, like the lizards that live on the banks of the river that make my skin crawl at a touch, strange and cold. It seems focused on the panel, jabbing at it over and over with frustration, always eliciting the same result a big orange message. I remember a wall panel in Uncle Tos’ house bearing similar letters, he claimed it was salvaged from a ship he called Devore. I remember him scoffing at the thought of them. The two exchange words as they work, referring back and forth to their devices, little grey cubes that beep and whir and flicker with a rainbow of lights, buzzing like firebugs at a particularly interesting flower. They seem pleased as the device shrieks in a high-pitched tone and their screens turn a green shade, different messages flickering on their screens.

The wreck begins to whine again. It’s deafening in the crawlspace and I clutch my ears, barely biting my tongue before a cry of pain escapes my lips. Through my tear-filled eyes, I can see the two here are as unbothered as the mountain men outside, I feel as though the bird one’s meat hook beak is piercing my eardrums. The walls of my small hiding hole begin to shake and rattle, the wreck must be preparing to launch another tiny star.

The wailing becomes unbearable, I fear I might scream or cry but I cannot even hear my ragged breaths begging for release.

Then there is silence, a chatter and clatter of beaks and hissing sounds from the two below but sweet silence from the tiny star manufacturer. Then their chattering voices cease too. Had they heard me heaving gulps of air into my lungs? Could I be at the mercy of aliens? My Great-grandmother never had any advice for aliens, and my mother’s lectures on cooking and cleaning would be of no use here. Nor would my Uncle’s barrel laugh nor my father’s gigantic stature. I have only myself here in this place I was forbidden to step. If I ran back to the village offering my quivering knees to warn of the aliens I would be in trouble. If I slunk back, heavy with lies that I had never been here the seekers who were surely following the shooting stars would be caught unawares.

I draw a deep breath.

And before I can choose the floor falls away and I crash to dark, metallic ground.

Bravo Fleet

Bravo Fleet