‘Mayday, mayday. Does anyone read?’

For the umpteenth time, she sat at the shuttle’s cockpit and transmitted the message. For the umpteenth time, there was no response.

At the shuttle’s aft, the bundle of blankets on the deck stirred. ‘Can’t you automate it?’ the bundle said.

This gives me something to do. Instead, she said, ‘I’m varying the frequency. Seeing if anyone picks up. Every moment, we’re closer to Federation territory.’

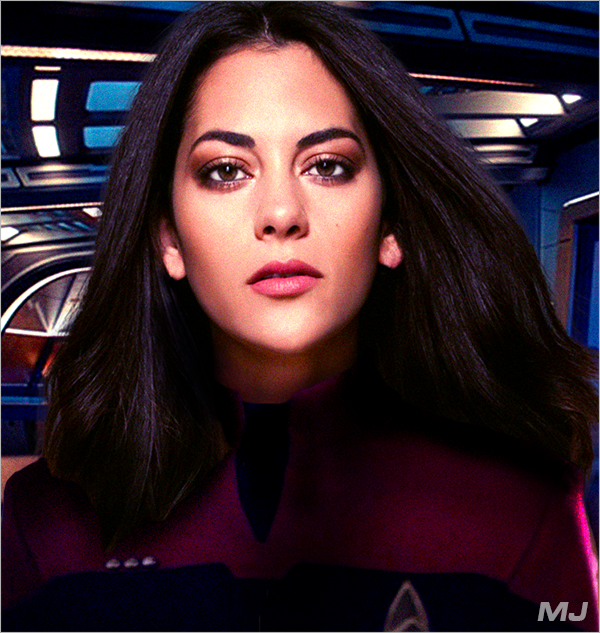

‘Kilometres closer. Light-years away. Valance…’ The blankets were thrown aside, and Olivia Rivera sat up, rubbing her eyes. ‘I think we need a new plan.’

Days. Days they’d been out here, deep in the furthest reaches of the Midgard Sector, with their warp drive out. It had been by sheer chance that they’d been on board the shuttle Tristan when Ihhliae and Endeavour had been caught in the gravitational pull of the anomaly. A snap-second judgement that had prompted Valance to launch them into the subspace corridors rather than stay nestled in the shuttlebay, a decision that had almost killed them when they’d at once taken a hit in the debris field. But they’d seen the Ihhliae explode only moments later, and the blast had knocked them out of the subspace tunnel and back into normal space.

Normal space, tens of light-years from their origin point. Nowhere near Starfleet support. Nowhere near anyone, it seemed. And their warp drive was out.

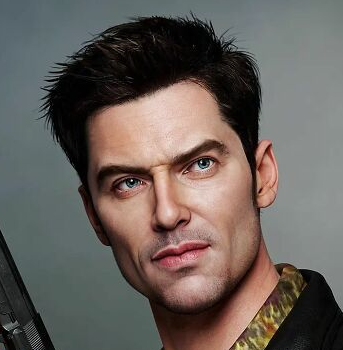

Valance spun around on her chair, giving Rivera a flat look. ‘A new plan? This is Plan A, B, C, everything. Fly towards Federation territory. Keep transmitting. We should have enough power for our signal to reach Gateway. Someone will pick it up. And they’ll get here.’

‘They should have picked it up.’ Blanket around her shoulders, Rivera slumped to the co-pilot’s chair. ‘They haven’t. They’d have replied. I think we need to take another look at the shuttle’s systems.’

‘I’ve done all the repairs I’m rated for. And some I’m not. And, again: we need a new power regulator. If I boost power much more to comms, it might overload. And if it overloads…’

‘We lose all other systems.’ Rivera slouched back. ‘Wishful thinking. Sorry.’

‘We’re fine for days, weeks, as we are,’ Valance reminded her, softer as she read the desperation. This was a journalist, she reminded herself. A civilian. Not someone who ever expected to find themselves stranded in deep space; not someone who had ever trained for this possibility. ‘But we took a hammering getting off the Ihhliae. Our top priority has to be keeping three systems online as long as possible: life support, comms, and emergency replicators.’

Rivera closed her eyes. Nodded. And slumped back into the fugue state of waiting she’d adopted not long after they’d emerged from the catastrophe. She had a talent for that, at least; for sinking into her own mind enough to be resilient against the absolute nothingness that survival was sometimes. It meant that Valance didn’t have to keep her focused, distracted, or stop her from losing her nerve.

It meant when she did speak, though, it was as if she’d been in deep thought for so long she’d forgotten Valance wasn’t party to the discussion going on inside her head.

‘What if,’ Rivera said, hours later, apropos of nothing and almost making Valance jump as she broke the silence, ‘we busted back in?’

‘In what?’

‘The subspace corridor. We were blasted out by the explosion. Could we get back in it? Find our way back the way we came?’

‘I’ve not picked up any readings suggesting there’s a subspace rift near us. And even if we could get back in, that’s probably more dangerous than being here.’

‘Maybe,’ said Rivera, then, ‘Could we make one?’

‘One what?’

‘A rift.’

Valance again looked at her. ‘Did you hear me? That’s just finding a different way to die.’

‘Do you prefer fast or slow ways to die?’ Rivera raised her eyebrows. ‘That’s not a rhetorical question.’

‘You’re still working on the profile?’

‘I’m considering if I’d rather blow myself up than wait for whichever way we’ll die – suffocation, freezing, or starvation – if we stick with this plan.’

Perhaps the civilian did need some managing. Valance set her hands on her knees. ‘Every hour we’re out here maximises the chance someone detects us or picks up our distress call. This is the best option. It’s the hard one, the one with no quick answers, the one where we feel helpless. But it is, I promise you, our best chance.’ She spoke without frustration, as gentle as she could manage without sounding insincere or patronising.

Rivera fidgeted with the corner of the blanket. ‘And every hour we’re out here, Endeavour is out there without you.’

Valance’s nostrils flared. ‘They know what to do. Kharth knows what to do. Right now, my responsibility is to this shuttle – my responsibility is to you.’

‘Are you saying you’re holding back on my account?’

‘No -’

‘If you were alone, what would you do?’

Valance hesitated at that. The thought had sincerely not occurred to her; since they’d finished diagnosing the Tristan’s condition and identified how lost they were, her path had been clear.

Rivera jumped on the pause, taking it for doubt. ‘There. You wouldn’t be waiting. You’d be figuring out some dangerous gambit to get back to your ship, or get back to Starfleet, because you’d be responsible to them more than you’re responsible to yourself.’

‘I know we’ve spent a lot of time together lately. I know it’s been your job to understand me.’ Valance spoke in a low, level voice. ‘But please don’t try to psychoanalyse me.’

‘I call it reading you. You don’t do well with helplessness. So you take responsibility. Which makes me the, the hamster you’ve adopted so you have some sense of control over something. Except I’m chewing on the bars right now and would rather take my chances breaking free and diving under the furniture to escape being trampled on.’

‘This metaphor’s gotten away from you.’

‘Little bit.’ Rivera shrugged, then clapped her hands together. ‘Come on. Let’s just brainstorm stupid ideas. Imagine this is a training exercise. What idea would you shoot down?’

‘I’ve already shot down all of your ideas.’

‘In theory. Not in principle. Busting back into the subspace corridor. How do we do it?’

Valance blew out her cheeks, thinking. ‘We’d have to assume the corridor exists even relatively close to our position in space-time. But we can’t control that. So, we’d need to cause a new rift in subspace.’

‘But the warp core’s out. What else aboard can affect subspace?’

‘We’d need something that could generate Cochrane distortions.’ Explaining it like it was first year Academy theory at least kept Rivera distracted.

‘Okay. What about our subspace transmitter?’

‘That’s millicochranes; that’s nothing,’ Valance sighed. ‘If we’d brought the Lancelot, we’d be on a Type-14 with metaphasic shields, but we’re not. Perhaps we…’ She stopped.

Rivera’s eyebrows shot up. ‘Perhaps…’

‘We do have microtorpedoes on board.’

‘We’re gonna shoot a hole into subspace with a quantum torpedo?’

‘No.’ Valance hesitated. ‘But perhaps with a tricobalt torpedo.’

‘Oh.’ Rivera’s expression flattened. ‘Oh, this is turning into an idea, isn’t it.’

‘An idea that could get us killed on numerous levels.’

‘I still vote for taking our chances with the subspace corridor -’

‘That destroyed the Ihhliae, might not even be near us, and could lead us to God knows where?’ Valance shook her head. ‘No. Blasting our way back into the subspace corridor is not an option.’

Rivera shot to her feet. ‘I am not taking the “sitting around and wait to die” option! Not if I have a choice’

‘You’re a civilian.’ Valance did not stand, looking up at her. ‘You’re a civilian on a Starfleet ship, on a mission over which I have authority. I’m sorry, but you don’t get a choice.’

‘Is this the “playing it safe” that’s characterised the back half of your career, except for the successful part of it?’

Valance bit her lip. ‘You’re not going to provoke me into taking action.’

‘Because this situation really feels like it needs guts-and-glory Valance, Derby Valance, not Paris Valance -’

‘That’s enough.’

‘Because nobody’s answering our comms, because they’re not powerful enough, and nobody’s out here, and nobody’s looking for us…’

‘That’s -’ The snap died, and Valance stared at her. Rivera stared back, obviously expecting – hoping for – an outburst, obviously surprised at how quickly it was smothered. ‘Okay.’

‘Okay?’

Valance stood. ‘I’m going to make some modifications to one of our tricobalt devices.’

Rivera watched as she padded towards the aft of the shuttle. ‘We’re actually doing my stupid plan?’

‘No.’ The ordinance was stored in the underbelly of the shuttle, accessible through a hatch at the aft. ‘But you’re right. Nobody’s picking up our comm signal. Which means we need to do something to get someone’s attention.’

‘Oh. We’re going to cause a big enough subspace explosion to catch someone’s attention?’

‘We don’t have that big a tricobalt device aboard. What do you think we are, a walking Khitomer Accord violation?’ Valance gave her a wry glance. ‘But with the right modifications, I can adjust a torpedo’s detonation parameters to produce a series of timed pulses.’

Rivera sat up. ‘An SOS. How long will that take?’

‘To modify? An hour. To be picked up?’ Valance shook her head. ‘It should be detectable across light-years. Theoretically from Gateway. But it requires someone to notice, and investigate, and get here.’ When she glanced up, Rivera had moved to sit next to the hatch on the deck. ‘What’re you doing?’

But she’d brought the toolkit with her. ‘Helping.’

An extra pair of hands did help. Even if all Rivera did was hold onto tools while Valance needed both hands. It was not a complicated modification, but it did need to be precise if she wanted it to work.

And still, an hour later, when they sat at the main controls and Valance fired the tricobalt device into the pitiless dark before them, the end of all their work was nothing more than a small burst of light in the distance.

‘I don’t know what I expected,’ Rivera mused. ‘I can’t see subspace.’

‘We’ve definitely done something,’ Valance assured her. ‘It’s lighting up on sensors. But now… we wait.’

‘And hope that if we do get someone’s attention, it’s the right someone.’

Waiting was easy for the first hour. Valance held position, because the last thing they needed to do was to light a signal fire and leave it, and so they sat in their chairs, feeling as if something might happen. It could have; a ship didn’t need to be tremendously close to be within even a delayed transmission distance.

At the end of the second hour, Rivera was slumped back into her bundle of blankets in the co-pilot’s chair.

‘Ask me something,’ she mumbled.

Valance looked over. ‘What?’

‘I’ve spent the last month crawling inside your skin.’ Her voice had gone small, tired. ‘Inside your head. And it might be my job, but right now we’re stuck together, and I was just a complete cow, using my knowledge in an unprofessional way.’

‘That’s… I’ve known experienced officers behave worse in comparable circumstances.’

Rivera’s lips curled. ‘You’re sweet. Does anyone ever tell you you’re sweet?’

Valance made a face. ‘Definitely not.’

‘You’re good at seeing what people need to hear. Mediocre liar, though.’

Despite herself, Valance gave a short laugh. ‘I mean it.’

‘Then you’ve known some bratty officers.’

‘That is… true. Fine.’ Valance paused. ‘Why’d you become a journalist?’

‘Oh, starting with the little ones, huh?’ Rivera thought a moment, dark eyes locked on the pitiless black of space beyond the canopy. She looked small in the bundle of blankets, Valance thought. Haunted. Faced, perhaps for the first time, with the notion of just how tiny they all were, mortal beings, against the vastness of the cosmos.

‘I like stories,’ Rivera said at last, voice soft. ‘But… real ones. Fictional ones are easy; they’re made to make sense. The world doesn’t make much sense. We have to make it make sense. Like… dying out here. What kind of sense would that make?’

‘It doesn’t have to,’ said Valance carefully.

‘But we can make it make sense to us. Dying together. What does that mean?’ Rivera’s gaze flickered to her, then away. ‘It’s like that with everything, my job.’

‘I thought you’d say something about the truth.’

‘The truth is relative. I don’t mean like… like facts. But what ties people up isn’t usually the specifics of events, it’s interpretation. Implications. Relevance. All I can offer – anyone can offer – is a way of figuring how all of that ties together. Not the truth. A… a framework for the truth.’

‘It’s all the same, isn’t it,’ Valance mused.

‘What is?’

‘What we want. What we all want. Connection.’ A sidelong glance at Rivera suggested she’d been wrong-footed by this conclusion, perhaps surprised at Valance’s philosophising. Throughout the interview, Valance had – sometimes consciously, sometimes not – presented the more pragmatic side of herself. ‘Is that the only question I get?’

Rivera gave a tight, pleased smile. ‘Fire away.’

‘Ever married?’

‘Keeping it light, I see.’

‘Finding meaning in how we’re dying together.’ Valance would not admit a perverse satisfaction from turning the tables, even though Rivera had opened the door specifically for some sense of fairness. Her motivations, wants, past and future had all been poked and prodded for the sake of this profile article. It wasn’t just that she was, she admitted, curious about the woman who had vivisected her for weeks. But the glint of a sense of reclaiming some power did help.

‘Once,’ Rivera said at length. ‘Divorced… oof. Six years ago? The career dragging me across the cosmos – never being in the same place to settle down – did not help.’

‘I… can relate to that,’ Valance admitted.

‘We’re still friends. A little less since she remarried.’ Rivera sounded wistful. ‘It’s hard to see someone build a life without you, like they packed you away and built a wall around you, and then they use someone else to paper over the cracks. I know that’s not how it works, but it feels like that. Sometimes.’

Some day, that would be Cortez, Valance thought. Vibrant, bubbly, people-oriented Isa Cortez would not be alone forever. Cortez had probably not been single for very much of her adult life, in fact; was the kind of personality to fall in love hard and regularly, love someone until their star went out… but then find another star.

‘That might be better than still working with them,’ Valance murmured.

Rivera was silent for a moment. ‘I never asked questions about that part of your life.’

‘I’m sorry, I wasn’t trying to pry more than -’

‘No, no. I put the pieces together. Besides – the narrative, the meaning, is all there in your relationship with Captain Aquila. It sounds cold, but… I didn’t need to repeat the same tune with you.’

Valance frowned. ‘What happened with Isa isn’t the same as what happened with Cassia.’

‘Isn’t it? Isn’t it the oldest story for people like us? We love hard, and we love true, but no matter who they are or how far we fall for them, they’re just… not what makes our sun come up in the morning.’

She could have been. Valance swallowed, not sure how she could answer. Not sure if she wanted to argue, fight for the relationship she’d abandoned. Not sure if she wanted to dissect her feelings with a more deft touch. Not sure if she wanted to banish them to the ether and ask something else.

So for one ridiculous moment, when one of the Tristan’s systems chirruped, her first feeling was relief at the interruption. Then she realised what was going on, and her heart lunged into her throat.

‘We’re getting a comm signal incoming…’

Rivera reached out at once. ‘It’s a ways out… looks weak.’

‘Boosting power.’

And for the first time in days, a voice rippled through the chamber of the shuttle Tristan that did not belong to Karana Valance or Olivia Rivera.

‘Shuttle Tristan, this is Captain Augustus Tycho of the USS Tempest. Chin up, star sailor. Cavalry’s here.’

Bravo Fleet

Bravo Fleet