The older woman’s name was Dazir, Valance discovered as they rode up front on the wagon trundling down the unevenly-paved, sandy road. She grew olive trees at her farm, which were pressed into precious oil that she sold at the market in the nearby town. From there, many barrels were sold on through the road and river network snaking across the country, the hard work of Dazir and her family shipped far and wide, or so the woman claimed with calm pride. She’d been making a local delivery with her two adult sons when their wagon had thrown a wheel and they’d struggled to fix it back into place, so her gratitude for the away team’s assistance was clear.

‘Sorry if we weren’t the most welcoming,’ Dazir said at last. This apology came only after a lengthy conversation, where Valance used every social skill she’d left frozen in ice to keep the other woman talking. ‘So many pilgrims coming from all over to here, where the Prophet first showed himself, that you can’t be too careful. Not everyone’s the holy sort.’

‘I just want to see for myself,’ said Valance, because it wouldn’t do to pretend to be too zealous about a faith on which she was profoundly ignorant. ‘Sometimes it feels like hope’s in short supply.’ It was a safe thing to say. Very few entities in the galaxy felt they were getting their due, and Dazir indeed grunted, steely eyes on the dusty way ahead. The road took them past clusters of red-tiled buildings and worked fields, with the squat brown shadow of the town lurking on the horizon some kilometres away still.

‘The Sun Lord teaches us to take care of ourselves and our own if we’re to help others,’ came the terse response. ‘I think too many folks forget that.’

In the back, Dazir’s adult sons sat on the casks with Gov’taj and Thawn, and were proving a little more philosophically loquacious.

‘…but how does anyone know he’s the Prophet?’ asked stocky Hollan, leaning precariously over the edge of the wagon with practised ease, strong arms holding him in place. ‘Anyone can walk in and spout scripture.’

‘Not anyone,’ countered his brother Mivel, long legs dangling off the back. ‘You couldn’t if your life depended on it, way you slept through the priest’s sermons last week.’

‘Unjust of you, Brother – I was working late to repair the south fence…’

‘Is it that simple?’ asked Thawn, bringing her knees up as she looked between them. ‘A man walks into the market, shows such a deep knowledge of scripture and the ills of some people, and we now think he’s the Prophet?’

They looked uneasy. ‘We’re not idiots,’ Hollan said a little hotly. ‘I don’t know how they do things in Rivarran, but we’re no bumpkins. We know a con man when we see one, and he did more than… I don’t know. Tell people he knew they were worried about the upcoming harvest, because everyone’s always worried about that.’ Rivarran was, they had surmised, a city to the distant east, and the location Dazir and her sons had assumed the trio had come from.

‘We’re curious,’ Gov’taj reassured them. ‘That’s all. It’s why we’re here.’

‘Folks should ask questions,’ Mivel pointed out. ‘Lord knows the church will.’

‘And what happens next, do you think?’ asked Thawn. ‘If the Prophet’s in the capital to see the Pontifex, if he is a Prophet…’

The two farmers exchanged looks. ‘Not for us to say any more than you,’ Mivel said at last with a shrug. ‘But if he’s been sent, he’s been sent for a reason. There’ll be changes, won’t there? The virtuous put in their rightful place. The overmighty struck down. It’ll be time that any one of us can commune with the Sun Lord, listen to his word and spread it, so long as we’re free from the trappings and distractions of indulgent wealth -’

Hollan leaned down to clip his brother around the back of the head. ‘Enough of that, or you’ll get yourself in trouble. The Prophet was welcomed to town by the church and Priest Riggoria. They weren’t going to do that if he was spouting your ascetic nonsense.’ His eyes fell on the other two, beady and suspicious. ‘You’ll have to see for yourselves.’ They said nothing more for the rest of the journey, the brothers wary of sharing too much after Mivel’s contemplations.

The sun was fat and gold in the sky when the wagon passed through the gated wall to reach the unevenly paved streets of the town. Its rays were enough to paint the pale, squat stone buildings even more yellow in the late afternoon light, but the streets fizzed with people in darker, coarse, and hardy travelling clothes, and greater in number than Valance would have expected for this cluster of buildings.

‘Pilgrims,’ Dazir grunted. ‘Everyone’s come flocking, looking for answers. You’ll have difficulty securing lodgings for the night.’ But she pulled up her wagon at the periphery of the town square and made no offer of further assistance. While she looked a little awkward about it, Valance simply gave a sincere smile. It could have been awkward to refuse.

‘We’ll make do.’

‘That you will. You know how to work to earn help. The right way.’ She glanced up and down the street. ‘If you want to see the heretic’s fate, you’ll want the north walls. Anyway, we better drop this off. Safe travels to you.’

‘We were fortunate,’ mused Gov’taj as the wagon with the three Drapicians and their wares trundled down a different turn, ‘to find such blunt assistance. But these people seem hard-working by nature.’

‘Cultures and peoples aren’t just one thing,’ Valance said, jaw tight, but she turned down the main street. ‘Let’s see about this heretic.’

The square itself was a bustle of evening life, even as stands from the market were tidied away, unsold wares loaded into crates and wagons. Most sellers had little left to pack, the influx of pilgrims for now booming local trade. Valance wondered if that would remain the case as more and more people came in, perhaps from further away, perhaps looking for difficult hope for which they were less able to pay. Drapes of bright colours hung from windows around the square, and even from the squat building of what looked like a town hall, but despite its hefty construction and the grand work of carved masonry around its doorways and windows, it was not what drew the eye.

By its tower alone, the church loomed over the square and the town alike. It had plainly received the lion’s share of quality stone and craftsmanship, shining golden in the late afternoon light, and a gleam in the belfry suggested more than one bell at the top of those highest reaches. Intricate carvings on the archways spoke of great skill in masonry, while the door itself was a darker wood than she could see elsewhere, likely imported at some expense.

But with the market ending, neither town hall nor church was drawing the attention of the gathered. Neither were any streets behind them that had a look of drinking houses or eateries. Dispersing from the town square, the crowd had begun to shuffle towards the north, just as Dazir had told them.

‘Why,’ murmured Thawn, ‘wouldn’t they execute someone in the town square? Especially a heretic?’

‘Perhaps they don’t kill people within the walls, or near the church,’ replied Valance quietly as they slipped into the back of the crowd. ‘This faith follows a lot of patterns observed by xeno-anthropologists, but let’s not make assumptions.’

The explanation came quickly. The gates to the north wall were open and led directly onto a sturdy stone bridge crossing the wide river. Burly figures in pale robes and cudgels lined up across the bridge, blocking the way, while behind them stood a trio of figures: another broad-shouldered Drapician in an ornate steel breastplate, a tall, thin man in rather fine robes bearing symbols they’d seen about the church, and a prisoner. Their hands were bound behind their back with rope, and tight bindings at their ankles let them only shuffle. A sackcloth hood had been tied around their head, but Valance’s jaw tightened as she took in the generic, simple clothing.

‘That could be one of ours,’ she muttered to Thawn and Gov’taj as they tried to get a good view through the clamouring crowd.

‘On it,’ Thawn murmured, slipping behind the big Klingon and adjusting her jerkin so she could discreetly consult her tricorder. Gov’taj obliged, helping her move to the shadow of a building to be better obscured as she worked.

Valance turned to someone nearby in the crowd, a sallow-faced Drapician woman who wasn’t in travelling garb like most others. ‘Is that the heretic?’ she asked.

The woman scoffed gently. ‘That’s what Riggoria says he is. Not sure his crime. Worrying Riggoria for getting too close to this so-called Prophet and asking questions?’ Despite a curt, dismissive tone, she still kept her voice down.

Valance leaned in. ‘We just arrived. I’ve only heard stories. Who is this Prophet?’

‘Long gone,’ the woman sighed. ‘You won’t get sight of him here. But whoever or whatever he is, he’s also how Riggoria will march into the capital and be seated at the right hand of the Pontifex, and nothing stops our local esteemed priest.’ She gave a sallow smile. ‘Sorry, Newcomer. Church politics are the same everywhere.’

Valance narrowed her eyes at the figure in the most ornate robes. ‘Is that Riggoria?’

‘No, Riggoria left with the Prophet. Sandton here is just reminding us all of our place.’ She shrugged. ‘Maybe he is a heretic, maybe he did try to hurt the Prophet. Not sure he needs drowning.’

‘They’ll just throw him in?’

‘Tied and bound and hooded. He’ll drown. It’ll be nasty. Anyway, I want a better view.’

The woman shouldered her way through the crowd, and Valance reflected glumly on how someone could question the justice of an execution they deemed politically-motivated, and still want to see it. She moved to the nearest wall and reached up to grab a windowsill, hauling herself up a few feet to get a better view. The waters beneath the river looked deep, the fading sunlight casting them into shadow. There was no way she could see to get past the burly enforcers.

When she dropped back down to street level, Thawn and Gov’taj were waiting for her. ‘He’s human,’ Thawn said, lips tight.

‘I don’t know if I can fight all of them,’ Gov’taj mused, eyeing up the row of enforcers. ‘But we can try.’

‘We have to maintain the Prime Directive above anything else. Every time we draw attention to ourselves, even a little, we threaten it,’ Valance hissed.

‘So we let him die?’ Thawn challenged.

‘I’m thinking, Lieutenant.’ Valance’s lips thinned. They could not allow anyone’s body to be found and studied, lest they realise someone among them wasn’t Drapician. But with the officer being dumped in the river to drown, the simplest and most callous option was to recover their corpse later.

What would Rourke do? she wondered with a flash of guilt. He probably would have left Thawn at the dig site and brought Dashell, and so had an anthropologist to help figure out how to navigate this problem. Or he’d come up with a dramatic physical rescue that might cause disruption but not make anyone think they were aliens. Or…

Her eyes flickered back to Thawn. ‘Transporters from orbit can’t reliably pierce the atmospheric interference. What about site-to-site from the Watson?’

Thawn hesitated. ‘Not easy. I’m not picking up a combadge. I’m going to have to calculate his position exactly if I’m going to connect my tricorder with the Watson’s systems and handle it remotely.’

Gov’taj frowned. ‘You cannot simply communicate with Commander Dashell, send him your tricorder readings, and have him do it?’

‘Even remotely, I’m better,’ Thawn said simply. She looked at Valance. ‘What about the problem of making him disappear in front of everyone?’

‘You won’t,’ said Valance, and winced. ‘You’ll wait until they drop him in the river. Then you’ll beam him out.’

Thawn’s eyes widened. ‘He’ll be moving, it’ll be all but impossible to calculate his exact location without any better study of the river flow, even with the tricorder scans – he might be moving pretty quickly or…’

‘Can you do it?’ Valance cut her off.

The Betazoid’s breath caught. ‘I suppose I have to, don’t I.’

‘Yes.’ Valance turned to Gov’taj. ‘Find her somewhere discreet and hidden. I’ll keep watch and an open comm, so you know when they throw him in. Move fast; we might not have long.’

Even as her two officers peeled off, heading for quieter streets further away, Valance turned to the gathering and the bridge just as the holy man the local had called Sandton stepped up to speak.

‘Friends! Faithful!’ He raised his hands, and almost at once Valance understood that this was not the spiritual leader of the local town, that he was only the right hand to the priest Riggoria. There was a waver to his voice, and the attention he commanded of the crowd was not absolute. They were curious in their own right, not spellbound by him.

Still, he had a spectacle and a group of armed enforcers, and that counted for a lot as he spoke on. ‘You have come here to see justice. We live in a time of revelation. Only days ago were we graced by an emissary of the Sun Lord, come to ease our pains as foretold, possessing deep knowledge that only one of the chosen could possess.’

Near Valance, someone coughed. On the other side, two old women continued nattering with each other. Discreetly, she slipped her hand into the folds of her disguise and tapped the combadge to open a channel for Gov’taj and Thawn to hear.

‘Our blessed guide Riggoria has taken the Prophet to the Pontifex, so all might hear his words, and all might hear the message. We will enter a new era of light and hope. But there stand among us enemies – enemies of that hope.’ Sandton’s words faltered a little as he pulled himself out of clunky rhetoric. Cutting to the chase with a hint of shame, he waved a hand to his left. ‘Behold, heresy!’

Heresy looked more like a bound and hooded figure, but whoever they were, they knew they were being addressed, shuffling their feet and struggling against the grips of the man in the breastplate. They did not, however, speak.

‘They have chosen silence since we cast them into the cells, for they know their forked tongue would show them an agent of evil,’ Sandton hollered, a little more in his stride now he had something to rail against. ‘But he came to our fair town when we sheltered the Prophet himself and was seized trying to slay him! And how can we bring faith and light if we do not cast down shadow!’

It sounded to Valance like an officer whose combadge – whose universal translator – had been ditched or taken. But that was a question for later, as Sandton grabbed the hooded human by the shoulder and pushed them towards the edge of the bridge. ‘Stand by,’ she muttered into her own combadge, nestled inside folds of her jerkin.

If Thawn needed more time, she could not communicate that – and Valance could not give it.

‘As the Sun Lord cast the dark gods to the deepest depths upon his ascent, so do we cast down those who stand against him.’ Sandton sounded much happier full of fire and brimstone, and he clutched the human by both shoulders now. ‘Behold, judgement! Behold, justice!’

There was the briefest struggle. It was not the simple act Sandton had likely hoped for. The human tried to break free, got one shoulder loose, turned to push back at Sandton. But then the man in the breastplate intervened, and both Drapicians bodily shoved the hooded human over the side of the bridge. There was a gasp from the crowd, a splash – then nothing.

‘Now,’ Valance hissed into her combadge under the hubbub of the audience.

The crowd was pushing forward, and now the enforcers let them as they raced to the riverside and the bridge. Valance moved with them, heart thudding in her chest, aware of so much that could go wrong – that Thawn might fail, or that someone might spot the lights of a transporter. But as the sun sank deeper behind the rooftops of the town, the wide river’s fast waters settled into an inkier darkness.

Perhaps, by the time she got to the side of the bridge and could look down, there were bubbles. Perhaps there was a shadow. But there was no sign of outside interference and, with her heart in her throat, Valance knew that was the most important thing. She just had to hope she hadn’t stood by and watched a fellow officer die.

It took a few minutes for her to find Gov’taj and Thawn. They had skipped back a few streets and found a narrow alleyway with a cart they could shroud behind. And still, when she got there, Gov’taj was pinning down a struggling, bound, hooded, soaking wet figure whose muffled gasping was incomprehensible, and an irritable Thawn was fiddling with her bag.

‘If you just – give me a moment, please!’ she pleaded.

Valance pushed past, kneeling. ‘Here,’ she said curtly and reached to her side for the knife she’d made sure to bring. From there it took seconds to cut the bindings, and the figure at once relaxed, and stopped thrashing so she could reach up for the hood. ‘You’re safe. You’re with friends.’ She pulled the hood off and stared. ‘What the hell?’

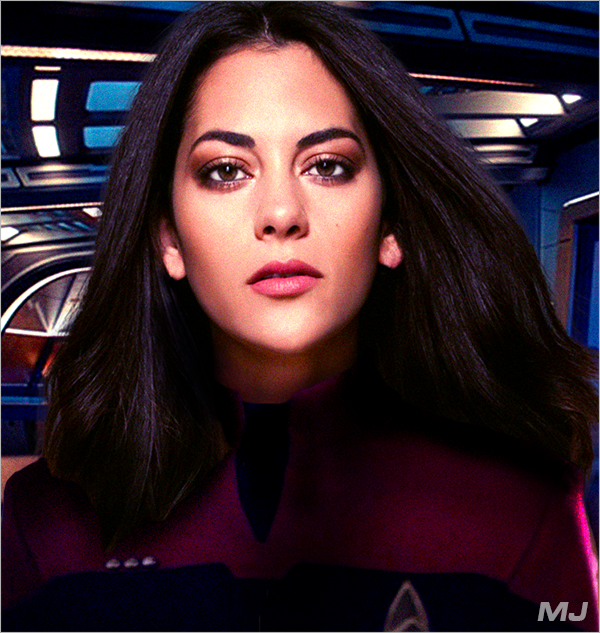

Thawn’s breath caught. ‘Beckett?’

He looked like a Drapician because he, too, had received the same genetic modifications to infiltrate the local society. But he couldn’t summon a response at first, doubling over and trying to both evacuate his lungs of river water and gasp for breath at the same time. Only at length, on his hands and knees, still dripping wet, did Nate Beckett finally rasp, ‘I gotta say, Commander. You’ve got great timing.’

Bravo Fleet

Bravo Fleet