The USS Victory dropped out of warp, taking up a high, cautious orbit above the plane of the system, sensors reaching down to the waiting pirate flotilla. The pirates loitered in the shadow of a ragged asteroid belt: three escorts, ugly improvised constructs, moving lazily around an old B’rel bird of prey.

“King of the bloody lanes,” Hardy murmured.

Kincaid answered him from the executive officer’s chair. “Remember, captain” he said, “the Klingon was useful to us earlier. Better the devil you know. But he’s changed his ship, that bird of prey wasn’t part of the group before.”

“Aye, well,” Hardy said. “Let’s see how diplomatic we can be.”

He drew a breath, straightened, and nodded to comms. “Open a channel. Let’s see if royalty listens.”

The channel hissed, popped, and then stabilised. Hardy cleared his throat.

“This is Captain Odysseus Hardy of the Federation starship Victory,” he said. “We’re right on time. I believe your king owes us a conversation.”

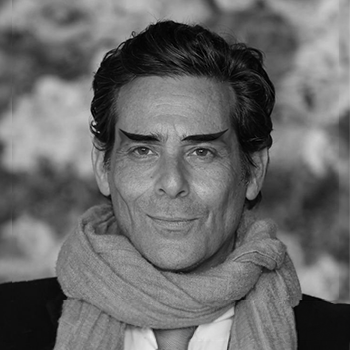

For a moment there was only static and then the screen flickered, and the king appeared on the bridge of his bird of prey, looking distinctly more Klingon than Hardy had read in Ayres’ logs. He was older than Hardy had expected. Klingon age could be hard to place, but the silver in the long hair and the deep lines around the eyes spoke of decades spent in battle. The cloak he wore over an ancient, faded uniform fell across his shoulders like a second, heavier skin. His ridges were sharp and asymmetric: a white scar cut across one, puckering down towards his cheek. He looked, Hardy thought, like a man who had survived too many wars and not enough peacetime.

“Starfleet,” the king said, in that same rough, amused voice. “You keep your word. That is surprising.”

“My name is Captain Hardy,” Hardy said mildly. “And you are still ‘the king’?”

“For you, for now.” The king’s mouth quirked. “Names carry a complicated history.”

“Fortunately,” Hardy replied, “I’m rather fond of complications. They make the galaxy far more interesting. How will I know how to sing your praises or curse your name if I don’t know what it is”

Something like respect flickered in the Klingon’s eyes. He leaned forward, the movement brought the light up under his brow, catching in the small golden pins pounded into his cloak clasp.

“You are not the one I dealt with before, Hardy,” he said. “Where is Ayres? The quiet one with the tired eyes.”

“Missing,” Hardy said, keeping his tone level. “Along with his first officer. Their ship has been half-stripped by your favourite cultists, their crew scattered, and the Victory has inherited the mess. So here we are.”

The king grunted. “They survived longer than most.”

“I intend to improve that statistic.” Hardy inclined his head a fraction. “You sent Ayres a set of coordinates. Orantei. You forgot to mention the station was about to declare independence from sanity.”

The Klingon’s smile thinned. “When we spoke, it had not yet slipped its leash.”

“You knew it was an artificial intelligence,” Hardy said. “And you knew the Pilgrims were manipulating it with their reliquaries.”

The king studied him for a heartbeat. “Such a ‘pretty’ word for a weapon. A deception worthy of a Romulan!”

“‘Weapon’ is a bit bald, isn’t it?” Hardy said. “I’ve seen what these things do. It’s uglier than that. Weapons at least imply someone pulling a trigger. This feels more like an infection.”

The Klingon laughed once. “Perhaps you are not an idiot, Captain Hardy.”

“High praise,” Hardy said. “Now. Let’s do the complicated bit. Who are you really?”

There was a pause. The king’s eyes went distant, then returned, sharper.

“I was once called K’halek, son of Morag,” he said. He spoke the name like a man testing a knife he had not used in years. “In another life.”

Hardy filed it away. K’halek. The past tense did not escape him.

“And what happened to K’halek?” he asked.

“He discovered that serving a house not worth the blood under its banner is a waste of a good death.” The Klingon’s mouth twisted. “I was an officer once. KDF. Battles with you, Starfleet, and many more besides. When the battles ended, and I returned home, I found my house traded our glories for petty political power. I called it surrender. A leash!” He shrugged. “I objected. Loudly. They offered me a choice: silence or exile.”

“So you made your own banner,” Hardy said.

“I was not prepared for my saga to end,” K’halek said, “so I chose to write my own.” He gestured broadly. “This is how I started. This old ship. Older than me. And then I built my empire out here. Decades, Hardy.”

“And now someone else is undermining it,” Hardy said quietly. “The Pilgrims.”

“Not someone,” K’halek corrected. “Something. The Pilgrims are fleas on the back of a beast they cannot see.”

“You’ve had contact with them,” Hardy said.

K’halek’s eyes cooled. “More than contact.”

He reached down; when his hand came up, he held a cube.

Even through the screen, Hardy felt his neck muscles tighten. The reliquary sat on the Klingon’s palm, no bigger than a child’s toy. Its black surfaces drank the light. For a horrible moment he thought he saw something move inside it, a suggestion of depth that could not exist in so small a volume.

“We took it off a transport,” K’halek said. “Seven years ago, before the Pilgrims called themselves that. Those preachers offered us the same bargain they offer everyone: give up your freedom, join their road to paradise, become part of the song.” He bared his teeth. “I do not take orders from fanatics and their trinkets!”

“You killed them,” Hardy said.

“Some,” K’halek replied. “Some we left on their ship. With this.” He turned the cube between thumb and forefinger. The movement was almost gentle. “I wanted to see what would happen.”

“Curiosity,” Hardy said. “Not always a virtue.”

“No,” K’halek agreed. “The next time we saw that ship, it was not as we left it. The hull was wrong. The power readings were wrong. The crew inside were wrong. Their eyes did not belong to them any more. The box had eaten its way into the metal and into their thoughts. They expressed little emotion as we boarded them and I killed them all..”

He closed his fingers around the cube, as if to restrain it.

“You kept one,” Hardy said.

“Of course,” K’halek said, mildly. “The beast does not show you its weaknesses on first meeting. It is wise to learn its habits.”

Hardy nodded slowly. “And? What have you learned?”

“That it is old,” K’halek said. “Older than our empires. Older than your Federation. It is not a thing that thinks in territories and borders. It thinks outside the normal patterns of transportation. It wants the trading lanes, not because of the ships that fly them, but because of the way those paths braid space together. Every reliquary is a hook. Every station they infect, every ship they take, adds another knot to an ancient net.”

“And the Pilgrims?”

“They are its hands.” K’halek smiled, briefly and without humour. “If your god promised to make you a finger of fate, would you not feel important? They think they are shepherds. They are livestock.”

Hardy let out a slow breath. It was one thing to suspect this. Another to hear it from someone who had watched it unfold over years.

“Why tell us all this?” he asked.

“Because they are closing my game,” K’halek said simply. “They have made routes I have controlled for decades into empty spaces where everyone fears to tread. They have turned stations that would let a pirate in for a quiet drink into temples that do not let anyone leave. When I steal from someone, I want them to curse my name and come after me next time seeking revenge and glory! The Pilgrims leave no-one behind to swear vengeance. Where is the purpose in that?”

Hardy found himself almost liking him.

“We want the same thing, then,” he said. “To break their net and to allow the people of the Expanse to pursue their own destinies.”

“To keep them free,” K’halek corrected. “Free will! The will to chase for petty reasons as much as grand rivalries!”

Hardy inclined his head. “You’ve been following their movements longer than we have. You’ve seen them develop, expand. Rather than just pointing us in directions, why don’t we work together?”

K’halek regarded him for a moment, eyes hooded. The cube sat now on the table between his hands, quiet and obscene.

“You have already seen one node,” the Klingon said. “Orantei. There are others. Little places they – what was your human word? – infect! A trading post that stopped trading. A deep-space buoy that began to broadcast hymns instead of hazard warnings.”

“Let us work together to dismantle them,” Hardy said. “I’m a different man than Ayres. I see no point in caution here. I want to take the fight to the Pilgrims.”

K’halek grinned, showing a mouth full of uneven, unashamed teeth. “Ah. There is the Starfleet I remember from my glorious past! Very well, Captain Hardy. For now, our roads go in roughly the same direction.”

“One more thing,” Hardy said.

K’halek raised an eyebrow.

“You called it a beast,” Hardy said. “The thing behind the reliquaries. The pattern. What do you think it wants? Beyond nets and songs and broken stations.”

K’halek’s gaze slid, for a moment, past Hardy, as if seeing something further off.

“It wants to wake up,” he said. “And it does not understand that the galaxy is not how it was before. It belongs to us, not them. And now you and I shall fight to keep it!”

The channel closed with a soft crackle.

Bravo Fleet

Bravo Fleet